A Life Unveiling Nature's Tiny Wonders: The Legacy of Dorothy Hodgkin

11 Mar 2025

Dorothy Hodgkin's life unfolded like a captivating scientific detective story. Born in Cairo in 1910, she was surrounded by a family that cherished exploration. Her mother, a botanist, instilled in her a love for the natural world, while her archaeologist father sparked a curiosity for unraveling mysteries. Despite the limitations placed on women in science at the time, Dorothy's passion for chemistry burned brightly. Fueled by books like "Concerning the Nature of Things," she devoured knowledge about the then-nascent field of X-ray crystallography – a technique that would become the key to unlocking the secrets hidden within molecules.

“I was captured for life by chemistry and by crystals.” - Dorothy Hodgkins

She created a personal laboratory in an attic room of the family home in Beccles, Suffolk. Here she gathered natural history specimens and performed analyses on such things as garden soil, using a treasured chemistry set given to her by a family friend.

Early Career

Fueled by her passion for chemistry and support from her family and a dedicated teacher,, Dorothy set sail for Somerville College, Oxford in 1928. There, she delved into the world of molecules, choosing to investigate the crystal structure of dimethyl thallium halides for her final year project. This project became the springboard for her lifelong fascination with crystallography.

After graduating, Dorothy's talents landed her a coveted spot in J.D. Bernal's lab at Cambridge. Here, she pursued her PhD, focusing on the crystallographic analysis of steroid crystals. This research on biologically important molecules became her life's driving force.

However, a shadow loomed over her scientific journey. In 1934, during her PhD, Dorothy sought medical advice for persistent hand pain. The doctor diagnosed her with "ulna deviation," a hand deformity caused by swollen knuckle joints. Despite being advised to rest, Dorothy's dedication to science compelled her to postpone recovery to complete critical experiments.

That same year, Dorothy returned to Oxford, her academic home, to take up a position at Somerville College.

Decades of Discovery

While working with J.D. Bernal, she was introduced to the power of X-ray crystallography. This technique, akin to a magical lens, allowed her to peer into the intricate structures of molecules, revealing their atomic architecture.

X-ray crystallography is a scientific technique that enables researchers to decipher the three-dimensional (3D) structures of biochemical compounds. X-ray beams pass through crystalized samples which generate specific diffraction patterns. These diffraction patterns are analyzed to determine the structure of the compound in the sample.

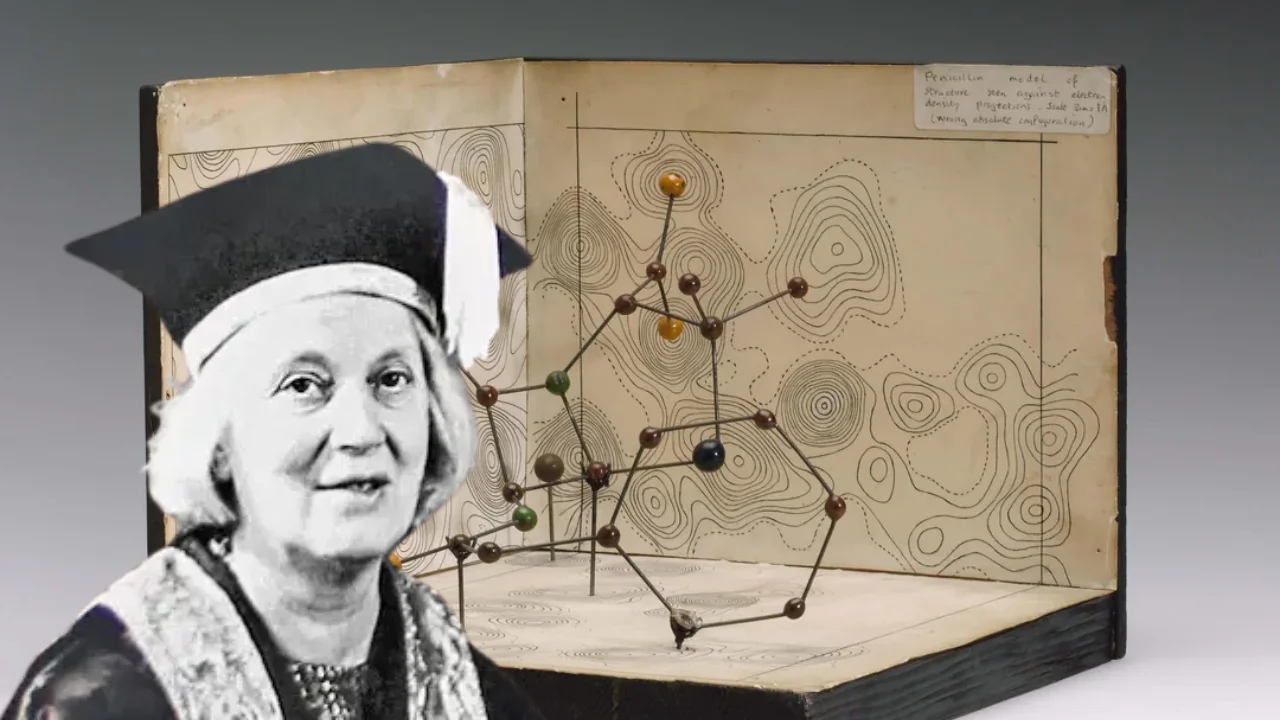

Molecular model of Penicillin by Dorothy Hodgkin, c.1945. Front three quarter. Graduated grey background.

[Molecular model of penicillin built by Hodgkin using the electron density contour maps behind the model.]

Unlike most scientists who focused on simpler molecules for X-ray crystallography, Dorothy craved a challenge. She set her sights on the complex giants of the biological world, her first target being cholesterol.

Years of meticulous research culminated in a breakthrough – she became the first person to determine the complete structure of a complex organic molecule using X-ray crystallography. This wasn't just an academic achievement; it paved the way for a deeper understanding of cholesterol's role in the human body.

The world faced a different kind of challenge during World War II – infectious diseases. Penicillin emerged as a beacon of hope, but its structure remained a mystery, hindering its mass production. Dorothy, ever the problem-solver, knew she had to be part of the solution. She embarked on a race against time to decipher the intricate dance of atoms within the penicillin molecule. In 1945, her persistence paid off. Dorothy unveiled the structure of penicillin, a critical step that allowed for its mass production, saving countless lives.

This victory was even more remarkable considering Dorothy's battle with rheumatoid arthritis, diagnosed in her late twenties. Due to her passion for her work and unwavering strengh, she devised ingenious workarounds, using levers to operate equipment when her hands became too swollen.

Unto her next discovery, she turned her attention to vitamin B12, a complex molecule shrouded in mystery. This time, she had a new weapon in her arsenal – computers. The early computing machines, guided by Dorothy's expertise, tackled the complex calculations needed to decipher the structure of this complex molecule The breakthrough came in the 1950s, which helped reveal the secrets of vitamin B12 and it’s role in human health.

But Dorothy's greatest scientific conquest was yet to come. For over three decades, she dreamt of unraveling the structure of insulin, the key hormone regulating blood sugar. It was an "impossibly complex" quest, as she described it. The limitations of X-ray crystallography at the time seemed insurmountable. Yet, her persistence carried on.

Finally, in 1969, with the help of her dedicated team, Dorothy achieved the seemingly impossible. Working tirelessly for three days straight, they built the model that unveiled the structure of insulin. This breakthrough revolutionized the treatment of diabetes, paving the way for mass production and improved insulin therapies.

Dorothy's life wasn't confined to the lab. She was a woman of strong convictions, deeply troubled by the growing threat of nuclear war and social injustices. She became a vocal advocate for peace, campaigning tirelessly for disarmament and serving as president of the Pugwash Conferences for a record-breaking term. Her compassion extended beyond borders, as she fostered scientific collaborations with researchers across the globe, including China.

First British Woman to win a Nobel Prize in any of the three major Sciences

In 1947, Dorothy was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, followed by the prestigious Royal Medal in 1956 and the Order of Merit in 1965 – the highest civilian honor in Britain.

In 1964, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognized Dorothy's groundbreaking work. But for her, the true reward was the impact her discoveries had on the lives of others. Her Nobel price win propelled Dorothy into the international spotlight. Invitations to conferences and events across the globe poured in.

Source: Britannica

Despite her worsening arthritis, Dorothy's dedication remained unwavering. She generously shared her time and expertise, maintaining a demanding international schedule for the rest of her life. Family members often accompanied her on trips, and a wheelchair became her trusted companion at conferences when walking became too difficult.

Dorothy retired from public life in 1988 and passed away in 1994. Beyond her scientific prowess, Dorothy was known for her kindness, humility, and generosity. Her colleague, Max Perutz, beautifully captured her essence at a memorial service: "She radiated love – for science, family, friends, students, crystals, and her college. This love was intertwined with a brilliant mind and an unwavering determination to succeed, even as her body weakened. There was a magic about her person."

Lessons from the life of Dorothy Hodgkin

Resilience in the Face of Adversity: Dorothy's journey was marked by challenges – limited opportunities for women in science, a battle with rheumatoid arthritis, and the pressure of groundbreaking research. Despite these hurdles, she never let them deter her from her goals. Her story exemplifies the power of perseverance and the unwavering spirit needed to overcome obstacles.

Passion and Purpose: Dorothy's life was a testament to the transformative power of passion. Her love for chemistry fueled her groundbreaking discoveries, from unlocking the structure of penicillin to unraveling the mysteries of insulin. Her story reminds us that when driven by a deep interest and a desire to make a difference, we can achieve remarkable things.

Compassion and Collaboration: Dorothy's impact extended beyond the lab. She was a woman of strong convictions, deeply concerned about social justice and the threat of nuclear war. She actively campaigned for peace and fostered scientific collaborations across borders. Her life reminds us that scientific progress thrives when coupled with empathy and a desire to connect with others.

To learn more about Dorothy Hodgkin and her life read: Dorothy Hodgkin : A Life by Georgina Ferry

A snippet of the book:

Dorothy Hodgkin was an eminent crystallographer whose research contributed to an extraordinary period of scientific discovery. She was also passionate about international affairs and an active peace campaigner. This biography reveals the inner life of a strong and passionate woman.