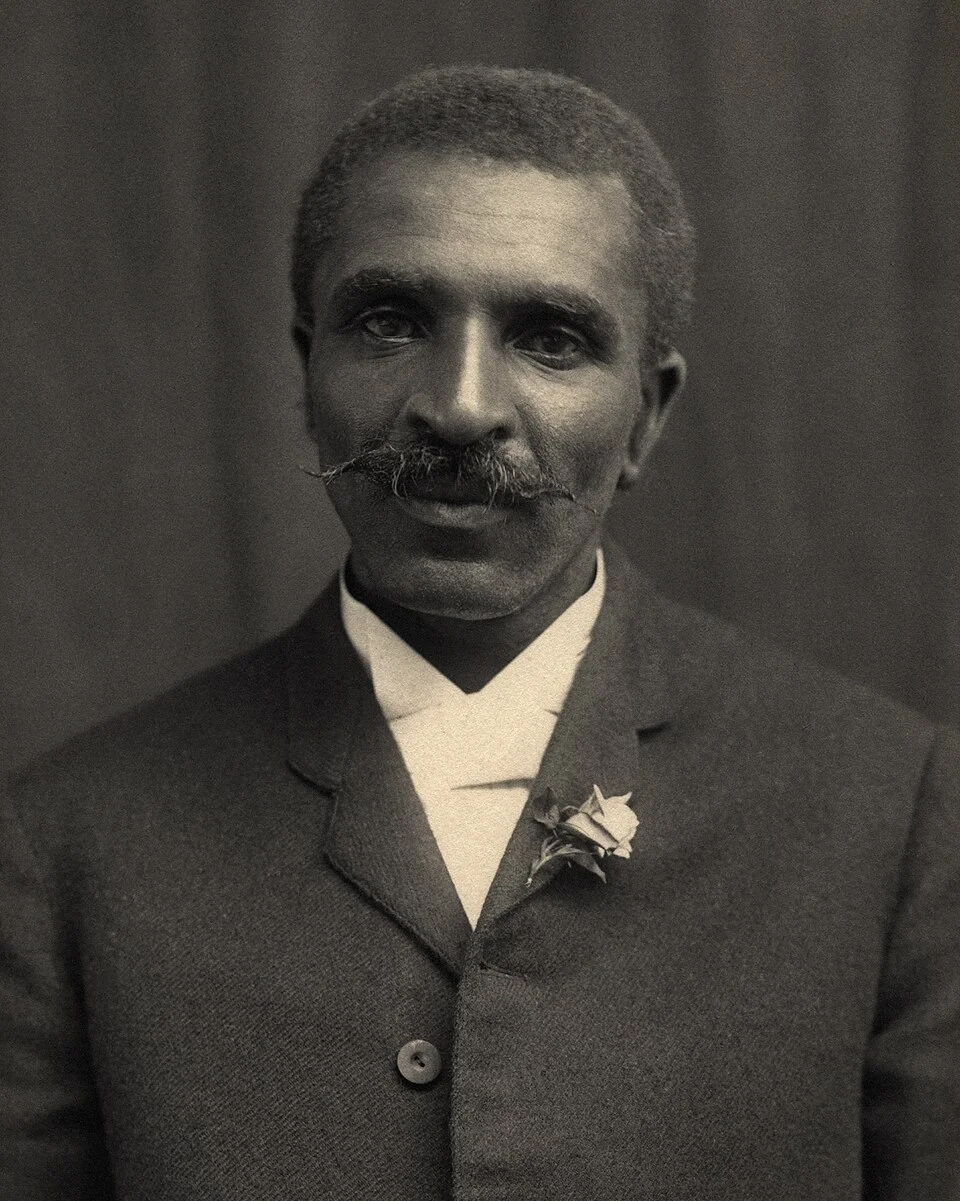

Life and Lessons With George Washington Carver; The Man who transformed Southern Agriculture

20 Jan 2025

Born into slavery in the early 1860s, George Washington Carver defied the odds to become a revered agricultural scientist and inventor. Overcoming a tragic childhood that saw him lose his family, Carver dedicated himself to improving the lives of farmers, particularly in the South after the Civil War.

His passion for plants led him to develop new techniques for soil improvement and introduce alternative cash crops, forever transforming the region’s agricultural practice for the better. Recognized for his brilliance, Carver became the director of the Tuskegee Institute’s agricultural department, establishing it as a research center, and even earned the distinction of being the first African American to have a national monument built in his honor.

Early Life

George Washington Carver’s life began tragically. Born into slavery to Mary and Giles, his father died before he even arrived. A week later, while still an infant, George, his mother, and sister were kidnapped by raiders in Arkansas. Thankfully, Moses Carver, the man who enslaved his parents, managed to retrieve George, but his mother and sister remained lost. After slavery ended, Moses and his wife, Susan, took George and his older brother, James, in and raised them as their own.

Despite the circumstances, George’s thirst for knowledge was nurtured. Susan, his adoptive mother, instilled in him the basics of reading and writing. However, racial segregation forced him to attend a school for Black children 10 miles away in Neosho. At 13, seeking better educational opportunities, he moved to Fort Scott, Kansas, but he had to leave the city after witnessing a black man get killed by a group of white people.

source: wilipedia

Carver persevered, attending various schools before finally graduating from Minneapolis High School in Kansas.

Education

Right from a tender age, George Carver had a deep passion for education, he walked eight miles daily to attend the Lincoln School for Negro Children, established by the Freedmen’s Bureau. After his high school diploma and to fulfill his desire to become educated, he applied to study at several colleges before he got accepted at Highland University in Highland, Kansas, but, when he appeared in person to register, the school refused to admit him because he was Black.

Faced with this challenge, Carver had to change course. He turned his attention to homesteading, staking his own claim on land. Here, he built a small haven for his love of plants and flowers, creating a conservatory. He wasn’t idle though – he diligently plowed the land, planting crops like rice, corn, fruit trees, and even forest trees. Despite these efforts, his thirst for education remained strong. In 1888, demonstrating his unwavering determination, Carver secured a $300 loan from the Bank of Ness City to pursue his studies.

Then later, in 1890, Carver started studying art and piano at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa. He met his art teacher, Etta Budd, who recognized his talent for painting plants and flowers. She encouraged him to study botany at Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames.

Carver was the first black student at the Iowa State Agricultural College, where he started studying in 1891. At the college, he carried out numerous research, and some of his works in plant pathology and mycology gained him his first national recognition and respect as a botanist.

Also, while doing his Bachelor’s degree at the Iowa State Agricultural College, Carver was encouraged and convinced by professors Joseph Budd and Louis Pammel to do his Master’s degree at the same college. He later received his Master’s degree in 1896 and also taught as the first black faculty member at Iowa State.

He was occasionally addressed as a “doctor” during his lifetime, but he never received an official doctorate. Before his death, Simpson College and Selma University awarded him with an honorary doctorate of Sciences.

Career Life

Carver’s academic journey began at Iowa State, where he held the distinction of being the first Black faculty member. However, in 1896, his path took a significant turn. Booker T. Washington, the esteemed leader of the Tuskegee Institute, invited Carver to head its agricultural department. Recognizing the immense potential, Carver accepted the offer, where he spent 47 years teaching.

During Carver’s leadership, the agricultural department blossomed into a vibrant research center. He instilled knowledge in generations of Black students, empowering them with self-sufficient farming techniques.

He championed crop rotation methods, a crucial practice for maintaining soil health. Recognizing the South’s cotton dependence and the negative decline the south soil was experiencing, he introduced alternative cash crops, offering farmers new economic opportunities. He also designed the “Jesup Wagon,” a mobile classroom that brought agricultural education directly to farmers.

After Washington’s death in 1915, Carver’s focus shifted. With fewer administrative demands, he dug deeper into research, experimenting with new uses for peanuts, sweet potatoes, soybeans, and other crops. This period also saw him gain national recognition. He addressed the Peanut Growers Association and testified before Congress, advocating for an import tariff on peanuts. These events propelled him into the national spotlight, solidifying his reputation as a renowned agricultural scientist.

Personal Life.

Throughout Carver’s lifetime, he never married. However, at 40, he started a courtship with Sarah L. Hunt, an elementary school teacher and the sister-in-law of Warren Logan, Treasurer of Tuskegee Institute. The relationship only lasted for three years.

Aside from his relationship life, he was a believer in God and science. He found a way to integrate both into his life. He also led a bible class for students at their request on Sundays at Tuskegee in 1906

Carver was unconcerned with wealth. He regularly refused raises in salary, and frequently the treasurer at Tuskegee had to beg him to cash his paycheck so the school’s books could be balanced.

Although Carver faced many racial discrimation in his day, he never dettered from teaching about Harmony and interracial scientific collaboration.

“If I use my energy struggling to right every wrong done to me, I would have no energy left for my work,” he once said.

Scientific Contribution and Achievements

When Carver became the head of agricultural research at Tuskegee in 1896, he saw a big problem. Farmers in the South kept planting only cotton, which wore out the soil and made it useless. This wasn’t good for anyone! Carver knew he had to help.

He had an idea. He suggested farmers plant peanuts and soybeans instead of cotton. These special plants, called legumes, could actually improve the soil while providing protein for people to eat. It was a win-win!

The soil in Alabama turned out to be perfect for peanuts and sweet potatoes too. But there was another hurdle. Even though these crops were better for the land, farmers couldn’t sell them easily.

Carver wasn’t one to give up. He got busy in his lab, figuring out new ways to use peanuts and sweet potatoes. He invented hundreds of products – peanut milk, flour, even ink and soap! This made these crops much more valuable, giving farmers a reason to grow them.

He founded an industrial research laboratory, where he and his assistants worked to popularize the new crops. They did original research and promoted applications and recipes they collected. Carver distributed his information as agricultural bulletins.

By 1914, with the cotton industry struggling, more and more farmers started growing peanuts, sweet potatoes, and using Carver’s inventions. Worn-out land was brought back to life, and the South became a major supplier of new farm products. Peanuts, once a forgotten crop, became a top seller, especially in the South.

Carver’s work helped Southern farmers break free from relying only on cotton. He showed them how to protect their land, grow new crops, and even turn those crops into valuable products. This helped farmers, especially Black sharecroppers, become more financially secure.

His works were recognized by notable individuals like President Theodore Roosevelt, Professors James Wilson, and Henry Cantwell Wallace before he became a public figure. Even the American industrialist, farmer, and inventor William C. Edenborn grew peanuts on his demonstration farm and consulted with Carver.

I love to think of nature as unlimited broadcasting stations, through which God speaks to us every day, every hour, and every moment of our lives, if we will only tune in and remain so.” – George Washington Carver, Letter to Hubert W. Pelt (February 24, 1930)

In 1940 Carver donated his life savings to the establishment of the Carver Research Foundation at Tuskegee for continuing research in agriculture. During World War II he worked to replace the textile dyes formerly imported from Europe, and in all he produced dyes of 500 shades.

Legacy

Even before his death, a movement began to establish a U.S. national monument to Carver. On July 14, 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated $30,000 to the George Washington Carver National Monument west-southwest of Diamond, Missouri, making him the first African American to be honored with such a national monument other than a president. The U.S. 1948 commemorative stamps featured Carver.

Two ships, the Liberty ship SS George Washington Carver and the nuclear submarine USS George Washington Carver (SSBN-656), were named in his honor.

Places like the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, the National Inventors Hall of Fame, and the 100 Greatest African Americans acknowledged Carver.

Lessons Learned From George Carver Washington.

Perseverance amidst adversity: Carver had a tough beginning as a child born into slavery and got orphaned as an infant. Even though this is a circumstance that can cause tremendous setbacks in one’s life journey. Nevertheless, he chose to trust God to help him overcome the difficulties he experienced. Also, his passion made him hold on to this purpose in life. Most importantly, he also learned and practiced how to take ownership of the trajectory of his life and desires amidst obstacles.

Education and lifelong learning: Carver’s life teaches us that learning and seeking knowledge are essentials of life. He demonstrated this by quenching his thirst for knowledge by pursuing education relentlessly. This passion for education moved him from town to town to put himself through school. His commitment to learning and education allowed making significant contributions to Agriculture and Science.

Impacting lives: One notable fact about Carver was that he helped improve farmers’ lives. Beyond his achievement, he established a positive impact through his agricultural advancement, impacting and improving the quality of poor farmers’ lives. Through his mobile classroom, “Jesup Wagon”, he educated people about agriculture and its importance.

No individual has any right to come into the world and go out of it without leaving behind him distinct and legitimate reasons for having passed through it.” – George Washington Carver

To learn more about George Washington’s Carver’s story read: George Washington Carver – A Biography by Gary R. Kremer

Book Snippet: This book strips away the myths surrounding the famed scientist George Washington Carver and portrays him as a brilliant, creative man who nonetheless possessed very human peculiarities and frailties.