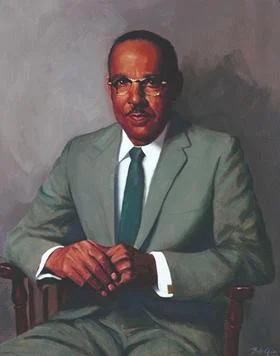

Vivien Thomas: The Unschooled Genius Who Transformed Medicine

10 Jan 2025

Vivien Thomas was famously known for his significant contribution in developing the procedure to treat Baby Blue Syndrome (a life threatening heart condition in infants). Thomas’s contribution to the medical field was unique because he lacked professional education and experience.

Thomas was an American laboratory supervisor born on August 29, 1910, in Lake Providence, Louisiana. He was born during the era of Jim Crow to his parents, Willard Maceo Thomas and the former Mary Alice Eaton.

Although Thomas was born in Louisiana, his family moved to Nashville, Tennessee, when he was about two years old.

Thomas started his formal education at Pearl High School in Nashville in the 1920s. He later graduated from the school in 1929.

While growing up, Thomas learnt how to do carpentry work from his father. During his childhood, Thomas and his brothers worked with their father in his workshop every day after school and on Saturdays, helping him do things like measuring, sawing, and nailing.

This Carpentry experience later assisted Thomas in securing a carpentry job at Fisk University, repairing facility damages after graduating high school.

Thomas was also an ambitious young man who desired to attend college and become a doctor. But, due to his family experiencing the Great Depression, he had to drop out from college.

Irrespective of the challenges surrounding him, Thomas intended to work hard, save money, and gain a higher education as soon as he could afford it.

Vivien_Thomas

Lesson 1: Overcoming adversity – Growing up wasn’t a smooth ride for Thomas and his family. The great depression affected their finances so badly. But regardless of the circumstances, Thomas was determined to pursue his dreams of going to a medical college and never gave up. Although he wasn’t able to attend one, he still managed to find his way into the medical field.

In 1930, through a friend, Charles Manlove, Thomas secured a job as a surgical research assistant with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Vanderbilt University.

On his first day of this job, Thomas assisted Blalock with a surgical experiment on a dog. Within a few weeks of helping Blalock, Thomas started conducting surgery on his own.

Sadly, Thomas was classified and paid as a janitor even though he was already doing the work of a postdoctoral researcher in the lab.

Thomas, even though he had a job, struggled with his finances. Although, he saved almost everything he earned. The salaries he received were not enough for him to comfortably quit his job and go back to school.

To worsen his situation Thomas’s savings got wiped out as Nashville banks failed. As a result of this, Thomas had to abandon his plans for college and medical school.

Lesson 2: Pursuing goals – Thomas’s challenge of not going to school could not stop him from pursuing his goals. Right from childhood, it has always been Thomas’ dream to build a career in medicines and he ended up being one of the cardiac surgeons in the field.

Thomas continued his job with Blalock. The duo did groundbreaking research into the causes and treatment of hemorrhagic and traumatic shock. Their research work later evolved into research on crush syndrome, which later helped to save the lives of thousands of soldiers on the battlefields of World War II.

While still at Vanderbilt, Blalock and Thomas began the experimental work in vascular and cardiac surgery, which laid the foundation for the revolutionary life-saving surgery they were to perform at Johns Hopkins a decade later.

Vivien Thomas spent 11 years working with Blalock at Vanderbilt before they moved to Johns Hopkins.

Initially, in 1941, Blalock took a job at his alma mater, John Hopkins, and requested that Thoman should come and join him over there. For Thomas, accepting to join Blalock at Johns Hopkins wasn’t easy. Thomas and his family faced numerous challenges, such as confronting a severe housing shortage and encountering a level of racism worse than they had endured in Nashville.

While at John Hopkins, Thomas learnt the surgical technique to correct the Tetralogy of Fallot, which he taught to Dr. Blalock. Thomas also created the surgical instruments to perform the surgery.

Lesson 3: Collaboration and teamwork – Thomas’s story demonstrated the power of collaboration and teamwork. Thomas teamed up with Dr Blalock and the duo did groundbreaking things in the medical field by leveraging on each others’ strength.

In 1944, the first blue baby surgery took place, with Thomas standing on a stepstool to coach Blalock over his shoulder. A PBS documentary, Partners of the Heart, and the HBO movie Something the Lord Made demonstrated this scene of the blue baby surgery.

The success of the surgical procedure changed the course of medicine. Unfortunately, Thomas did not receive any recognition for his contribution to the procedure due to racism.

Moving forward in 1946, Thomas developed a surgical technique to improve blood circulation for patients whose aorta and pulmonary arteries were transposed in a complex operation called an atrial septectomy.

Blalock got the chance to inspect Thomas’ completed procedure. According to Blolock’s remark, the procedure looked like something the Lord made.

source: .acc.org

For the rest of Thomas’ career, he spent 35 years at Johns Hopkins as a supervisor of surgical laboratories. Thomas was also involved in training many leaders in the emerging field of cardiovascular surgery.

Thomas was awarded an honorary doctorate by Johns Hopkins in 1976 for his numerous contributions. He was also appointed as an instructor of surgery at Johns Hopkins in its faculty of medicine.

Lessons 4: Hard Work pays off – Thomas wasn’t recognised and awarded for his contribution towards the blue baby surgery, but that didn’t weigh him down. Instead, Thomas continued to contribute to the field of cardiovascular surgery. He was awarded for his numerous contributions later on.

Thomas was married to Clara Beatrice Flanders in 1933. The couple had two children, Olga Fay, born in 1934, and Theodosia Patricia, born in 1938.

obitary

Viven Thomas died of pancreatic cancer on November 26, 1985, leaving behind his wife, Clara, their two daughters, and three granddaughters. Thomas wrote an autobiography about himself. The book was published after he died in 1985.