Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

ichef.bbci.co.uk

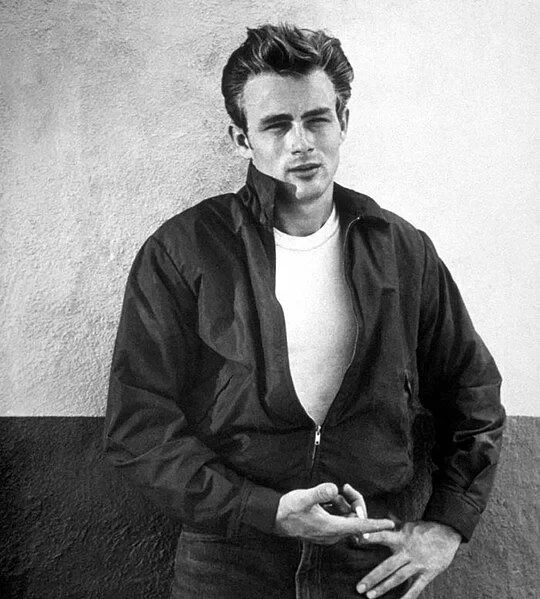

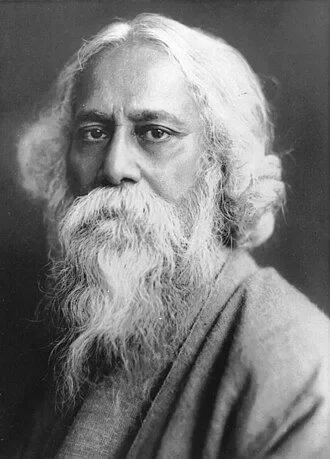

Athol Fugard

Birthday:

11 Jun, 1932

Date of Death:

08 Mar, 2025

Cause of death:

Cardiac Event

Nationality:

South African

Famous As:

Actor

Age at the time of death:

92

Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard 's Quote's

Early Life: Stories on the Edge of a Divided World

Athol Fugard didn’t just write plays — he chronicled the conscience of a nation. With a pen sharpened by outrage and empathy, Fugard exposed the raw wounds of apartheid-era South Africa and illuminated the complex humanity that endured within it. A playwright, director, actor, and witness, Fugard became a moral force in global theatre — not by shouting from a pedestal, but by listening, observing, and writing the truth as he saw it. Through simple settings and deeply human characters, he captured the dignity of the marginalized and forced audiences to reckon with injustice.

Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard was born on June 11, 1932, in the small town of Middelburg, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape. He grew up in Port Elizabeth, a port city that would later serve as the backdrop for much of his work. His upbringing was marked by stark contrasts: his mother, Elizabeth, was an Afrikaner and devout Christian who ran a general store and embodied resilience; his father, Harold, an English-speaking alcoholic and former jazz pianist, was emotionally distant but culturally influential.

It was a household where silence hung heavy, and observation became a form of survival. Athol, the only son, learned early to read the tensions in the room — a skill that would later underpin the emotional precision of his plays.

Though born into the privileged class under apartheid, Fugard’s earliest impressions were shaped by the everyday workers and Black South Africans who passed through his mother’s shop. These encounters ignited a sense of injustice that would smolder beneath his storytelling for decades.

A little-known fact: as a young boy, Fugard loved comic books and dreamed of becoming a race-car driver before theatre claimed his imagination.

Education: A Restless Mind, Unfinished Paths

Fugard enrolled at the University of Cape Town in 1950 to study philosophy and social anthropology. But he never completed his degree. Restless, inquisitive, and drawn to real life over academia, he left university to travel the country, even working briefly as a deckhand aboard a steamer ship — a chapter that deepened his empathy for working-class lives.

He later joined the Johannesburg Repertory Theatre and worked as a court clerk in a Native Commissioner’s Court, where he witnessed firsthand the brutal bureaucracies of apartheid. That experience left a permanent mark — the theatre of justice in South Africa was, in fact, a farce. His plays would become a protest against that performance.

Career Journey

Early Works: A Quiet Revolution Begins

Fugard’s first major play, “No-Good Friday” (1958), was performed by an interracial cast — a revolutionary act in apartheid South Africa. The government banned interracial performances, so Fugard and his collaborators staged plays in private spaces, sometimes illegally, sometimes at great personal risk.

In 1961, “The Blood Knot”, a play about two Coloured brothers — one light-skinned enough to pass as white — stunned audiences. With its intimate portrayal of race, identity, and brotherhood, it marked Fugard as a radical voice. He starred in the play himself, opposite Black actor Zakes Mokae — an act that defied apartheid law and drew the ire of the authorities.

Despite censorship, surveillance, and visa restrictions, Fugard continued to write and direct plays that documented the human cost of segregation. He often collaborated with Black South African actors and playwrights, including John Kani and Winston Ntshona, fostering a uniquely South African style of ensemble-driven theatre.

Global Recognition: Conscience on the World Stage

By the 1970s, Fugard’s work had reached London and New York, even as he remained under tight scrutiny at home. “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead” and “The Island” — co-written with Kani and Ntshona — drew international acclaim for their poetic indictment of apartheid and their subtle blend of humor, resistance, and tragedy.

In 1982, Fugard wrote “‘Master Harold’... and the Boys”, a semi-autobiographical masterpiece that explored the tensions between a white teenage boy and the two Black men who raised him. The play — deceptively simple in setting — packed a devastating emotional punch. It became one of the most widely produced anti-apartheid dramas worldwide.

Despite the global praise, Fugard remained grounded. He refused to become the “white liberal savior,” instead using his platform to amplify others, never losing sight of the stories that mattered most — the ones from home.

Later Career: The Chronicler of Change

With apartheid's collapse in the early 1990s, Fugard’s role as South Africa’s moral dramatist entered a new chapter. Some wondered whether his work would still resonate in the new South Africa. But Fugard evolved, shifting from resistance to reflection. Plays like “My Children! My Africa!” and “Valley Song” explored generational divides, memory, and the hope — and disillusionment — of the post-apartheid era.

He remained prolific well into his later years, even appearing in films like “Gandhi” (1982) and writing novels, including Tsotsi, which was adapted into the Academy Award–winning film of the same name.

Personal Life: Solitude, Partnership, and Place

Fugard was married to South African novelist Sheila Meiring Fugard, with whom he had a daughter, Lisa Fugard, now a writer herself. Though their marriage ended, the creative partnership endured in spirit. Fugard often spoke of his need for solitude — retreating to the Karoo desert or to his writing desk in Nieu-Bethesda, where he penned many of his works.

Despite international success, he chose to live most of his life in South Africa. “You can’t write about the dust unless you walk in it,” he once said. He remained a quiet presence — walking, observing, scribbling — while his plays traveled the world.

A curious tidbit: Fugard never formally trained as a playwright. He taught himself structure and rhythm by reading Chekhov, Beckett, and Tennessee Williams — all of whom would become stylistic touchstones in his work.

Legacy: Theatre as a Mirror, Not a Mask

Athol Fugard’s impact goes far beyond scripts and stages. He helped reshape global perceptions of South Africa and its people, not through polemic but through empathy. His plays gave audiences not just a window into apartheid’s horrors, but a mirror into their own humanity.

He is remembered as a literary dissident who stood up without preaching, a dramatist who believed the smallest human gestures could carry the weight of a nation’s struggle. Fugard made political theatre without ever writing propaganda — a balance few have achieved with such grace.

Today, his works are taught in classrooms, performed in theatres from Soweto to Sydney, and revered for their emotional honesty and quiet courage. He may have started as a boy from Port Elizabeth, but his voice became a global conscience.

In the end, Fugard’s legacy is simple but profound: he bore witness. And in doing so, he made sure the world couldn’t look away.

Name:

Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard

Popular Name:

Athol Fugard

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

Cardiac Event

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Middleburg, Cape Province, South Africa

Place of Death:

Stellenbosch, Western Cape, South Africa

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Advocate Quiet and mystical, yet very inspiring and tireless idealists. Athol Fugard is a quiet yet passionate idealist whose work reflects a deep sense of justice, empathy, and a desire to inspire meaningful change through storytelling.

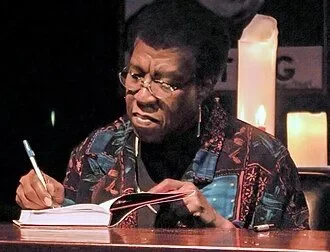

Athol Fugard is a renowned South African playwright whose works often highlight the struggles of apartheid and its impact on the people of South Africa.

Despite facing censorship and government opposition, Fugard continued to write plays that offered a sharp critique of South African society.

Fugard’s most famous play, "The Blood Knot", was first staged in 1961 and is considered a groundbreaking piece in post-apartheid theatre.

He founded the Serpent Players theatre company in 1956, which aimed to bring politically charged theatre to a segregated South Africa.

Among his honors are the Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement, several Obie Awards, and the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver from the South African government for his contribution to literature and human rights.

Athol Fugard has received numerous prestigious awards for his powerful work in theater, especially for highlighting the injustices of apartheid in South Africa.

His plays continue to be celebrated globally for their emotional depth and social impact.