Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

wikimedia.org

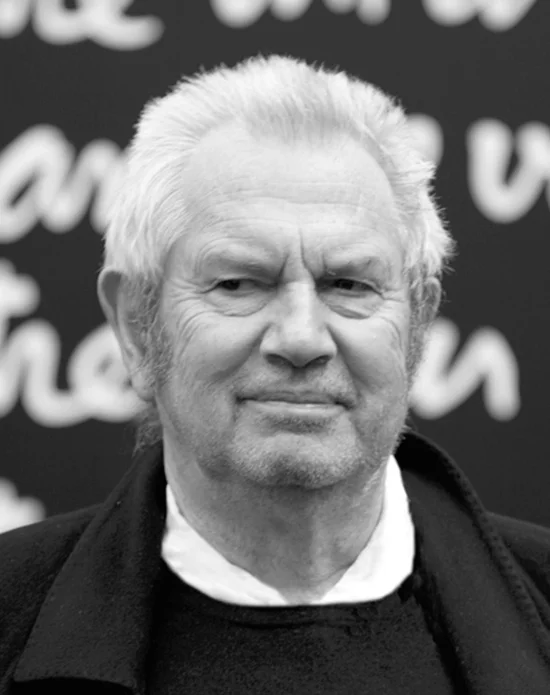

Ben Vautier

Birthday:

18 Jul, 1935

Date of Death:

05 Jun, 2024

Cause of death:

Gunshot Wound

Nationality:

French

Famous As:

French visual artist

Age at the time of death:

88

Benjamin Vautier 's Quote's

Early Life: Rootless Beginnings, Restless Curiosity

Ben Vautier never cared for boundaries — not in life, not in language, and certainly not in art. A provocateur, poet, and conceptual rebel, Vautier transformed the ordinary into the extraordinary, blurring the lines between art and life, humor and protest, sense and nonsense. Best known simply as Ben, he became a defining voice in postwar European avant-garde, famous for his handwritten slogans, absurd performances, and radical belief that anything — absolutely anything — could be art.

To walk into Ben Vautier’s world is to question your assumptions and laugh at your own seriousness. And that, for him, is the point.

Born Benjamin Vautier on July 18, 1935, in Naples, Italy, Ben’s early life was a blur of movement and contradiction. His father was French-Swiss, his mother Irish. He grew up speaking multiple languages but belonging fully to none — an outsider from the start. The family moved frequently during World War II, eventually settling in Nice, France — the city that would become Ben’s lifelong creative base.

As a boy, Ben was restless, curious, and allergic to conformity. School bored him. Authority annoyed him. He preferred drawing, collecting objects, and writing strange little phrases that puzzled and amused his friends. He once said, “I was born in Naples, but I was reborn in the chaos of my own ideas.”

A bit of trivia: as a teenager, he worked in a secondhand bookstore, where he was more interested in doodling on the walls than cataloging titles. It was here, surrounded by forgotten books and dusty corners, that Ben first imagined art as something beyond frames and galleries — as something living, breathing, and immediate.

Education: A Nontraditional Apprenticeship in Provocation

Ben had no formal training in art, and that was exactly how he wanted it. “Art schools,” he later quipped, “are where originality goes to die.” Instead, he educated himself through anarchist literature, Dada manifestos, and friendships with the misfits of the local art scene in Nice.

In the 1950s, he began creating “written paintings” — scrawled text on canvas or wood panels, often in black-and-white, bearing statements like “L’Art est inutile” (“Art is useless”) or “Je signe tout” (“I sign everything”). These weren't just clever quips; they were radical challenges to what art was supposed to be.

His influences were eclectic: Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, Yves Klein’s bold provocations, and the Zen spirit of John Cage. But Ben always insisted on his originality: “I don’t copy ideas. I steal them, transform them, and make them mine.”

Career Journey

The 1960s: Joining (and Bending) the Fluxus Movement

By the early 1960s, Ben had become deeply involved with Fluxus, an international network of artists pushing anti-art ideas through performance, play, and absurdity. With peers like George Maciunas, Nam June Paik, and Yoko Ono, Ben took part in events that blurred the line between joke and manifesto.

In 1962, he famously opened his own art space in Nice called “Magasin” — a hybrid gallery, shop, and artistic playground. He sold nothing and displayed everything, often curating exhibitions around paradoxes or provocations. A sign at the entrance read: “Everything is possible. Even the impossible.”

He became known for “actions” — spontaneous, irreverent performances that questioned not only the nature of art but also the ego of the artist. In one piece, he labeled objects in a room (“chair,” “table,” “art”) as if language itself were a sculptor. In another, he declared himself the author of all things: “I sign everything,” he said — and he did.

Ben’s insistence on authorship as a gesture was both playful and profound. “If I say it’s art, then it is,” he argued — decades before similar claims emerged from conceptual giants like Damien Hirst.

The 1970s–1980s: Expanding the Frame

As Fluxus waned, Ben continued to evolve. He created larger installations, more elaborate texts, and works that commented on politics, identity, and even art-world elitism. His pieces were shown across Europe and beyond, but he remained fiercely independent.

In 1972, he was one of the artists invited to Documenta 5 in Kassel — a major milestone that marked his transition from underground provocateur to internationally recognized conceptual artist. Still, he never lost his subversive streak.

Ben’s art became increasingly language-based, but always deeply visual. His works — usually scrawled in childlike handwriting — challenged viewers to read and interpret meaning themselves. What looked simple was often layered with irony, philosophy, and wordplay.

A lesser-known fact: Ben also composed experimental music, using silence, randomness, and repetition in the same way he played with words. For Ben, creativity was a loop, not a ladder.

Later Career: Mentor, Mythmaker, and Mischief Maker

Into the 1990s and 2000s, Ben became something of a cultural oracle in France — still irreverent, still playful, but widely respected. He mentored young artists, wrote columns, gave talks, and kept creating with relentless energy. His home in Nice became a kind of living museum, overflowing with signs, slogans, and chaos — a reflection of his mind.

In 2000, he was awarded the Officier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, one of France’s highest cultural honors. True to form, he joked, “Now I’m officially useless.”

His later work continued to challenge expectations. One of his most popular series includes phrases like “Contre tout” (“Against everything”) and “Rien n’est important” (“Nothing is important”) — reminders that Ben never stopped interrogating meaning itself.

Personal Life: The Artist as Observer

Despite his often loud and declarative art, Ben lived a relatively quiet personal life. He married fellow artist Annie Vautier, and they raised a family in Nice. Their home was — and remains — a vibrant labyrinth of works-in-progress, handwritten notes, and artistic detritus.

He was known among friends for his quick wit, restless mind, and habit of jotting down ideas at any moment — sometimes on napkins, receipts, or the back of his hand. He was never without a pen. Even dinner conversations could become performances.

Ben was also deeply interested in linguistic diversity, especially the defense of minority languages like Occitan and Basque. His activism in this space echoed his belief that language — like art — should never be dictated from above.

Legacy: Laughing at Limits, Living in the Margins

Ben Vautier’s legacy is one of joyful defiance. He made art that asked questions without demanding answers — art that poked holes in pomposity and turned everyday experience into a philosophical playground. He reminded the world that art is not only in the museum but also in the mirror, the sidewalk, and the absurdities of daily life.

Through handwritten phrases, absurd acts, and a refusal to conform, Ben helped redefine what art could be — and who had the right to make it. He gave voice to the outsider, the joker, the questioner.

Today, his works are part of major museum collections, but their spirit remains anarchic. Whether scrawled on canvas or whispered in conversation, Ben’s message is clear: everything can be art — even you.

Name:

Benjamin Vautier

Popular Name:

Ben Vautier

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

Gunshot Wound

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Naples, Italy

Place of Death:

Nice, France

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Debater Smart and curious thinkers who cannot resist an intellectual challenge. Ben Vautier was a fiercely inventive provocateur—irreverent, quick-witted, and endlessly curious—who thrived on challenging conventions and sparking fresh conversation by transforming the everyday into art.

Ben Vautier is best known for his handwritten text-based artworks that blur the line between visual art and philosophy.

Deeply influenced by Dadaism, his work frequently explores identity, ego, and the absurdity of modern life.

He was a key figure in the Fluxus movement, which celebrated randomness, performance, and anti-art ideals.

Vautier often challenged artistic norms by boldly signing everyday objects with “Ben,” declaring them as art.

Ben Vautier, a pioneering figure in the Fluxus and conceptual art movements, has received significant recognition for his innovative contributions to contemporary art.

One of his major honors includes the Grand Prix National de la Peinture in France, which celebrates his influential and boundary-pushing artistic practice.

Over the years, his work has been featured in prominent exhibitions worldwide, further solidifying his legacy as a provocative and impactful artist.