Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

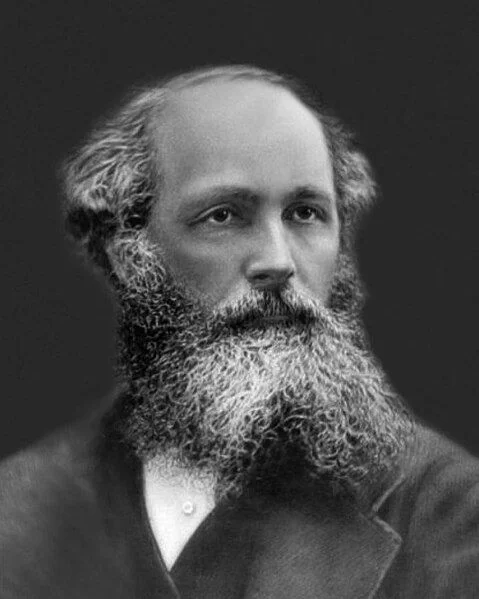

img.lemde.fr

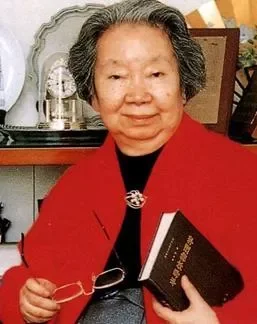

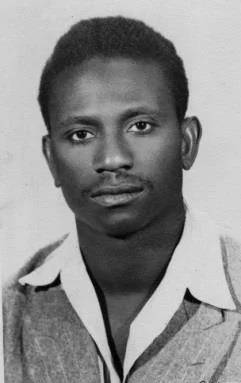

Cheikh Anta Diop

Birthday:

29 Dec, 1923

Date of Death:

07 Feb, 1986

Cause of death:

Heart attack

Nationality:

Senegalese

Famous As:

Anthropologist

Age at the time of death:

62

Seex Anta Jóob's Quote's

Early Life: Roots of a Rebel Thinker

Cheikh Anta Diop was a revolutionary mind who dared to challenge centuries of Eurocentric narratives and reimagine Africa’s place in the world. Fluent in the languages of physics and philosophy, history and linguistics, Diop blended disciplines with uncommon fluency to construct a bold, African-centred view of history. His mission wasn’t just academic but cultural, political, and deeply personal. He stood as a bridge between ancient African greatness and a future of renewed dignity.

Born on December 29, 1923, in the small village of Thieytou in Senegal, Cheikh Anta Diop grew up in a Wolof-speaking, Lebu family steeped in Islamic traditions and proud of their cultural heritage. Thieytou, while modest in size, had an ancestral pulse. It was a place where oral histories were cherished and the echoes of precolonial Africa lingered in the air. Diop's early years were defined by storytelling, rhythm, and respect for wisdom, a grounding that would shape his intellectual compass.

He was the kind of child who didn’t just ask what, but why—a question that would follow him into adulthood. “How did we come to be ruled by others? What happened to our past?” These weren’t abstract musings for Diop; they were deeply existential inquiries for a continent grappling with colonisation.

Education: The Making of a Polymath

In 1946, Diop left Senegal for Paris with a scholarship to study physics, but the City of Light offered more than laboratory benches. Paris was also a ferment of anti-colonial thought in the post-war years, and Diop immersed himself in this political awakening. He earned degrees in philosophy and chemistry and later enrolled at the Sorbonne for his doctoral work—an unusual path that mirrored his own hybrid intellect.

But it was in the dusty archives and academic salons of Paris where Diop began to unearth a truth that would shape his life’s work: that Africa had been systematically written out of history. His PhD thesis, initially rejected for being too radical, later became his seminal book: Nations Nègres et Culture (1955). It argued that ancient Egypt was a black African civilisation, laying the groundwork for a new Afrocentric historical narrative.

Diop studied nuclear physics under Frédéric Joliot-Curie, the son-in-law of Marie Curie, making Diop one of the few African scholars at the time with advanced training in the hard sciences.

Career Milestones

Pushing Against the Tide

Diop’s early career was a storm of controversy. In academic circles, his claims were dismissed as “political” rather than scholarly. But Diop, ever persistent, leaned into the rigour of multidisciplinary research, combining radiocarbon dating, linguistic analysis, and historical anthropology. He used science as a weapon of cultural recovery.

At a 1974 UNESCO symposium in Cairo, he famously debated prominent Egyptologists and held his ground with sharp data and a calm demeanour. His command of hieroglyphics and biological evidence stunned sceptics and won admirers.

Major Achievements: Building African-Centred Institutions

In 1966, Diop returned to Senegal, not to bask in accolades, but to build. He founded the Laboratory of African Prehistory at the University of Dakar (now bearing his name), where he introduced the first radiocarbon dating facility in Africa. His aim? To decolonise African history with African tools.

The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality remains a classic he wrote which advised Senegalese political leaders on how cultural identity could fuel development. He believed that true independence wasn’t just about borders but about consciousness.

Later Career: The Philosopher of African Unity

As he aged, Diop’s focus widened. He wrote about African federalism, unity, and even proposed a single African language based on Wolof. Though he never held high office, he became a guide to Pan-Africanist leaders and thinkers, from Kwame Nkrumah to Malcolm X. His voice was both grounded in data and soaring in vision.

Beyond the Mind: Personal Life

Despite his towering intellect, Diop was known to be soft-spoken, intensely private, and almost monk-like in discipline. He was married to Louise Marie Diop-Maes, a fellow intellectual and longtime partner in his cultural mission. He rarely sought the spotlight, preferring instead the sanctuary of libraries, laboratories, and quiet conversation.

Friends recall his love for jazz and his tendency to scribble notes in the margins of books late into the night. He lived modestly, more like a sage than a celebrity.

Legacy: The Man Who Gave Africa Back to Itself

Cheikh Anta Diop passed away in 1986, but his influence only deepened. Today, entire fields of Afrocentric historiography trace their roots to his work. His name graces universities, conferences, and Pan-African movements. More than anything, Diop gave black people, especially Africans, the permission to imagine themselves as descendants of greatness, not victims of fate.

In a world that had long looked down on Africa as a continent without history, Diop stood up and declared, with evidence and elegance, that Africa was the cradle of civilisation.

Name:

Seex Anta Jóob

Popular Name:

Cheikh Anta Diop

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

Heart attack

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Tiahitou, Senegal

Place of Death:

Dakar, Senegal

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Architect Imaginative and strategic thinkers, with a plan for everything. Cheikh Anta Diop was a visionary strategist and relentless thinker, whose quiet intensity and scientific precision fueled a lifelong mission to reconstruct Africa’s history with logic, evidence, and unshakable purpose.

He spoke multiple languages, including ancient ones

He trained under a Nobel-winning scientist: Frédéric Joliot-Curie

He wanted a unified African language

His PhD thesis was rejected twice

Cheikh Anta Diop’s work revolutionised African historiography by using carbon-14 dating to prove the African origins of ancient civilisations, particularly Egypt.

He also inspired the creation of numerous research institutes, schools, and scholarly prizes bearing his name.

He was the first to establish a radiocarbon laboratory in Africa, giving scholars the tools to scientifically date African artifacts and sites.

His groundbreaking book The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality became a cornerstone of Afrocentric historical thought and is still widely studied around the world.

In 1981, Senegal honoured him by renaming the University of Dakar as Cheikh Anta Diop University (UCAD)

In 1986, Senegal issued a national postage stamp in his memory, celebrating him as a cultural icon.