Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

img.apmcdn.org

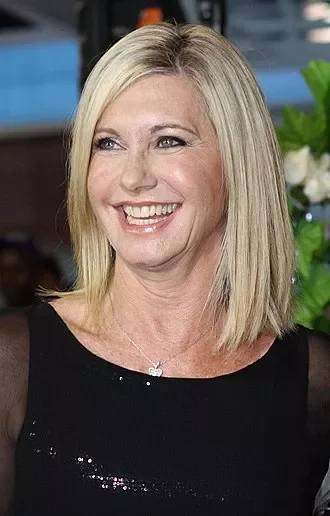

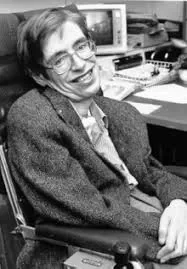

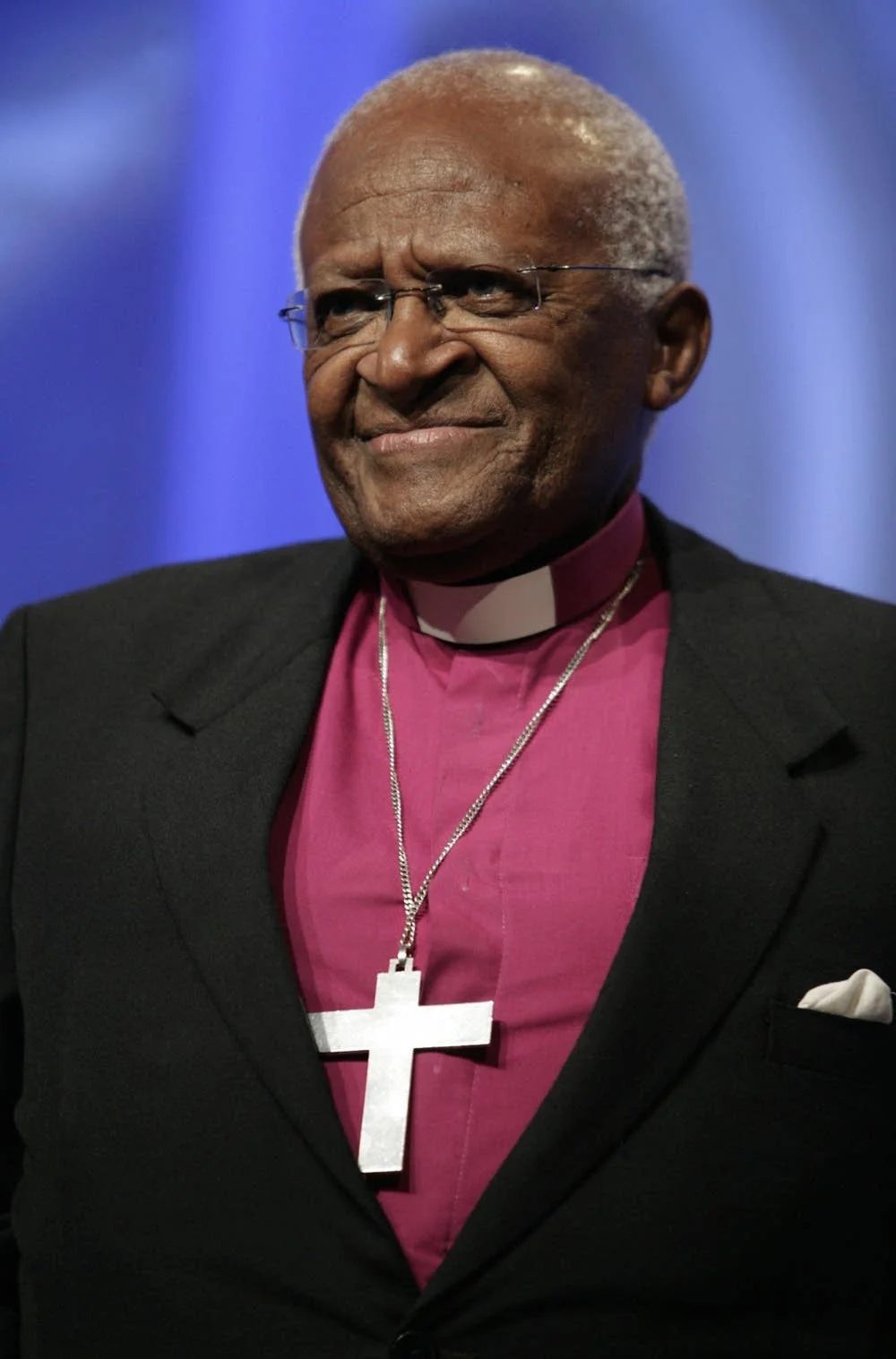

Desmond Tutu

Birthday:

07 Oct, 1931

Date of Death:

26 Dec, 2021

Cause of death:

Prostate Cancer

Nationality:

South African

Famous As:

Activist

Age at the time of death:

90

Desmond Mpilo Tutu's Quote's

Early Life: A Childhood of Contrasts

Desmond Tutu was a man who carried the weight of a nation’s pain, yet never let go of his infectious laugh. A spiritual leader with the heart of an activist, he wielded compassion as a weapon against injustice. Revered for his fearless opposition to apartheid and beloved for his boundless optimism, Tutu emerged as the moral compass of South Africa, one of the world's most enduring voices for human dignity.

Born on October 7, 1931, in the dusty township of Klerksdorp, South Africa, Desmond Mpilo Tutu entered a world stained by segregation and poverty. His father, Zachariah, was a schoolteacher—stern and principled. His mother, Aletta, was a domestic worker with a gentle resilience that left a deep imprint on her son. Though their lives were modest, the Tutu household pulsed with warmth, learning, and faith.

Tutu fell gravely ill with tuberculosis as a teenager. While hospitalised for over a year, he was cared for by a white Anglican priest, Father Trevor Huddleston, who treated him with rare compassion in a time when such empathy across racial lines was nearly unheard of. That experience etched itself into Tutu’s heart, planting the seeds of both his spiritual calling and his fierce commitment to racial justice.

Education: A Calling Ignited by Learning

Tutu initially followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a teacher after attending Pretoria Bantu Normal College. But in 1957, when the apartheid government imposed restrictions on Black education through the Bantu Education Act, Tutu resigned in protest. That act of defiance became his first public stand against injustice.

Turning to theology, Tutu studied at St. Peter’s Theological College in Johannesburg. He later won a scholarship to King’s College in London, where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in theology. His time abroad expanded his worldview and strengthened his belief that faith must be lived through action. In London, he also experienced a kind of racial equality that felt revolutionary—a glimpse of what his homeland could be.

Career: A Priest Who Preached Justice

Early Ministry and the Rise of a Voice

Ordained as an Anglican priest in 1961, Tutu quickly became known for his eloquence and intellect. But it wasn’t until the mid-1970s when he became Dean of Johannesburg (the first Black person to hold the position), that his voice began to shake the foundations of apartheid.

Clad in his clerical robes and armed with scripture, Tutu denounced the regime from pulpits and public platforms. He refused to be neutral. “If you are neutral in situations of injustice,” he once declared, “you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

Global Recognition and the Nobel Peace Prize

In 1984, at the height of apartheid’s brutality, Desmond Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. It was a recognition not just of his nonviolent resistance, but of his role as a unifier in a deeply fractured nation. As Bishop of Johannesburg and later as Archbishop of Cape Town (the first Black person to lead the Anglican Church in southern Africa), he became an international figure, tirelessly advocating for sanctions against the apartheid government and travelling the globe to rally support.

Despite death threats and government surveillance, he remained unflinching. He once insisted on flying economy class, even when travelling internationally, believing it was wrong to live in luxury while others suffered.

The Truth and Reconciliation Years

After apartheid crumbled, Tutu was appointed by President Nelson Mandela to chair South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1996. It was perhaps the most painful chapter of his career. Day after day, he listened to harrowing testimonies from victims and perpetrators alike, often weeping openly.

But Tutu believed in the healing power of truth. “There is no future without forgiveness,” he said, urging a divided country to walk the hard road toward unity. His approach wasn’t about forgetting the past—it was about confronting it with honesty and grace.

Personal Life: Joy, Family, and Playfulness

Despite his gravitas, Desmond Tutu never lost his childlike joy. He loved to dance. He cracked jokes sometimes mid-sermon. He laughed with his whole body, often so hard that tears streamed down his face.

He was married to Leah Nomalizo Tutu for over six decades, and together they raised four children. Leah was his steady partner who was strong, private, and unsparing in her support. Tutu affectionately called her “the boss,” crediting her with keeping him grounded.

He also loved gardening and was a huge fan of cricket, often slipping away from meetings to catch match updates. In a charming twist, he once appeared in an ad campaign for a South African fast-food chain, KFC, because he believed humour could unite people.

Legacy: A Beacon of Moral Courage

Desmond Tutu passed away on December 26, 2021, but his legacy radiates far beyond his life. He was not only a fighter for racial justice but a defender of LGBTQ+ rights, a critic of global inequality, and a tireless advocate for peace in places like Israel-Palestine and Myanmar. Even in retirement, he remained outspoken, famously rebuking his own church and political leaders when they strayed from the path of justice.

He left behind no buildings or monuments bearing his name, by choice. His legacy was not in stone—it was in the hearts he stirred, the wounds he helped heal, and the light he shone into some of humanity’s darkest corners.

In the end, Desmond Tutu was a spiritual insurgent, a joyful warrior whose greatest weapon was love. His life reminds us that courage doesn’t always roar; it sometimes laughs.

Name:

Desmond Mpilo Tutu

Popular Name:

Desmond Tutu

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

Prostate Cancer

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Klerksdorp, South Africa

Place of Death:

Oasis Care Centre, Cape Town, South Africa

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Advocate: Quiet and mystical, yet very inspiring and tireless idealists. Desmond Tutu was a deeply principled and empathetic visionary whose quiet strength and unwavering idealism inspired a nation toward healing and justice.

He once said he’d rather go to hell than worship a homophobic God, showing his bold stance on LGBTQ+ rights.

He signed off his emails with “God bless you richly” and often added smiley faces, even in serious messages.

Tutu loved The Lion King and joked that Rafiki, the wise baboon, reminded people of him.

Desmond Tutu played a pivotal role in the fight against apartheid, using his position as Archbishop and moral authority to advocate for nonviolent resistance and global sanctions against South Africa’s racist regime.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, recognising his tireless, peaceful opposition to apartheid.

Later, he chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a groundbreaking effort to help South Africa confront its traumatic past through restorative justice.

Over his lifetime, Tutu received numerous honours, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and honorary degrees from prestigious institutions worldwide, cementing his legacy as a global champion for human rights and dignity.