Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

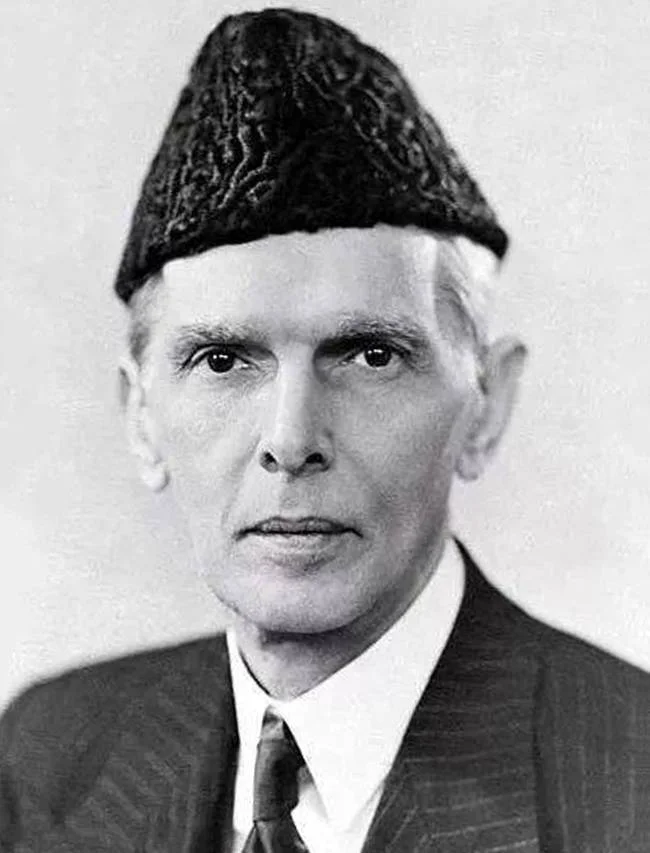

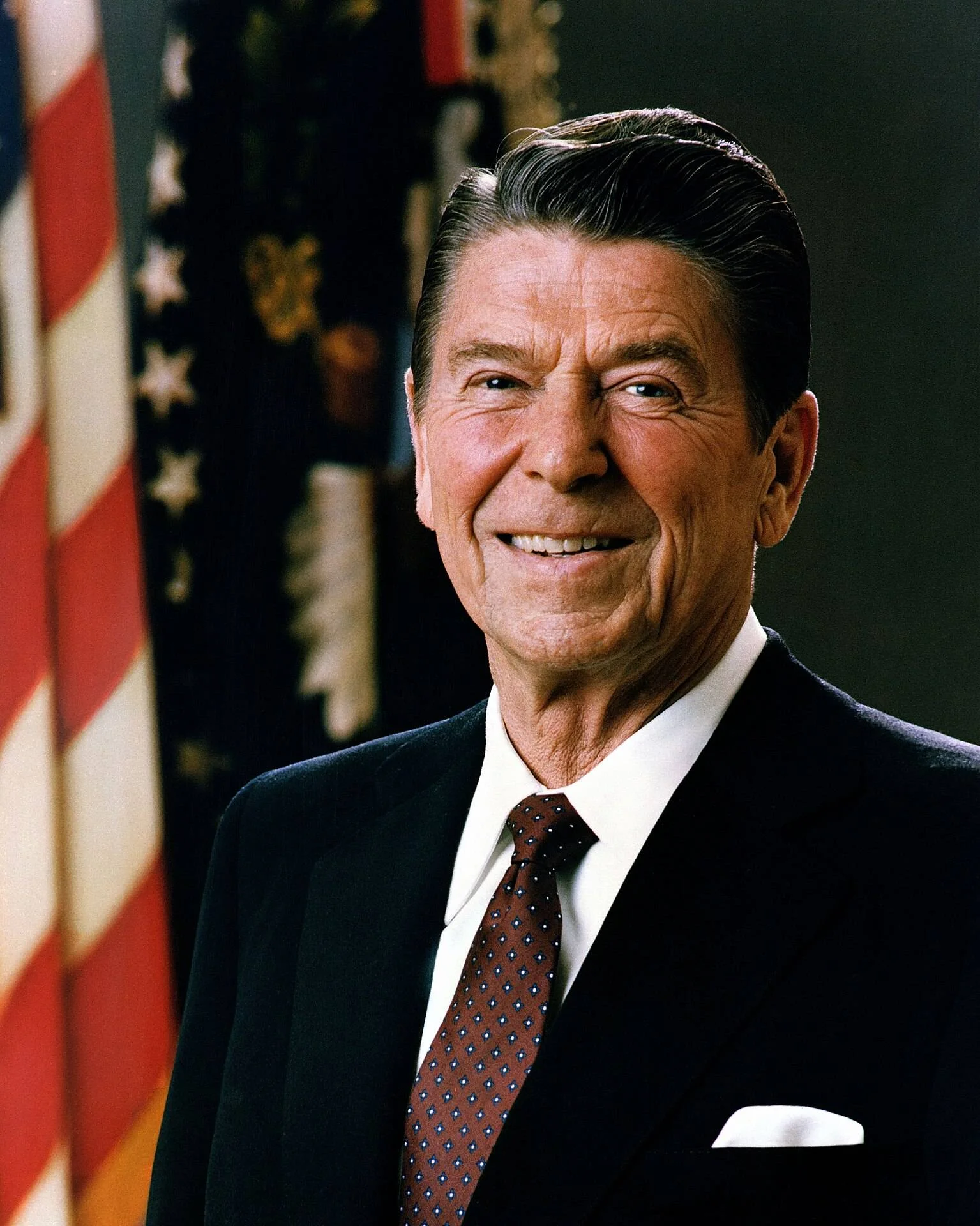

wikimedia.org

Hissène Habré

Birthday:

13 Aug, 1942

Date of Death:

24 Aug, 2021

Cause of death:

COVID-19

Nationality:

Chadian

Famous As:

Military Leader

Age at the time of death:

79

Hissène Habré's Quote's

Biography of Hissène Habré

Hissène Habré, often dubbed "Africa's Pinochet," was a Chadian politician whose time in power left a lasting and divisive imprint on his nation and beyond. Born on August 13, 1942, in the isolated town of Faya-Largeau in northern Chad, he grew up among shepherds in a family tied to the Anakaza branch of the Daza people, part of the broader Toubou community. His childhood unfolded against the harsh backdrop of the Sahel and the complexities of French colonial influence in Chad.

Early Life and Education

Habré showed a sharp mind from a young age. After finishing primary school in his hometown, he caught the eye of colonial officials, who helped him secure a scholarship to study in France. There, he enrolled at the renowned Institute of Higher International Studies in Paris, earning a political science degree. Those years abroad opened his eyes to global ideas about power and leadership, fueling his drive to take charge back home. Returning to Chad in 1971, he took a short stint as a deputy prefect before diving headfirst into revolutionary politics. His political path kicked off with FROLINAT, a rebel movement challenging Chad’s southern-led government. Habré climbed the ranks fast, leading the Second Liberation Army. But rifts within FROLINAT pushed him to break away and start his own group, the Armed Forces of the North (FAN), which later paved his way to the top.

Personal Life

Hissène Habré kept his personal world quieter than his public one. After fleeing to Senegal, he married Fatime Raymonde, and they raised four kids together. His family settled into life there, with Raymonde once saying their children felt more at home in Senegal than Chad. Even with his global infamy, Habré wove himself into Senegalese life, connecting with local Islamic circles.

Political Career and Rise to Power

Habré burst onto the world stage in 1974 with the "Claustre affair," when his fighters snatched several Europeans, including French archaeologist Françoise Claustre, and demanded ransom. It was a bold move that highlighted his cunning, though it soured ties with rivals like Goukouni Oueddei. In 1978, he stepped into Chad’s shaky government as Prime Minister under President Félix Malloum, but their alliance crumbled fast, dragging the country deeper into chaos. By 1982, with France and the U.S. backing him as a counterweight to Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, Habré stormed N’Djamena and claimed the presidency.

Rule and Legacy

From 1982 to 1990, Habré ran Chad with an iron grip, forging a one-party state under his National Union for Independence and Revolution (UNIR). His secret police, the Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS), became infamous for brutal human rights violations. On his watch, tens of thousands of Chadians—especially from ethnic groups he saw as risks—faced torture or death. Some estimates peg the death toll above 40,000. Yet Habré also steered Chad through the Libyan-Chadian conflict, scoring big wins in the Toyota War (1986–1987) that burnished his image as a clever military mind. Still, those triumphs couldn’t quiet the growing unrest over his harsh rule. In December 1990, Idriss Déby’s coup toppled him, sending Habré packing to Senegal.

Trial and Conviction

For years after his escape, survivors of Habré’s regime fought relentlessly for justice. In 2016, an African Union-supported court in Senegal found him guilty of crimes against humanity—like rape, torture, and mass slaughter—and locked him up for life. It was a groundbreaking case, the first time one African country judged another’s leader under universal jurisdiction. Many cheered it as a human rights win, though others pointed out it fell short on compensating victims.

Death and Legacy

Hissène Habré passed away on August 24, 2021, at 79 in Dakar, Senegal, after catching COVID-19 in prison. His death drew a line under one of Africa’s most notorious dictatorships, yet left lingering questions about justice for those he harmed. Habré’s story still splits opinions. Some credit him with shielding Chad from Libyan overreach, while far more see him as a figure of raw cruelty and oppression. His trial broke new ground in holding leaders to account, but it also laid bare the unfinished work of making things right for survivors of his regime’s

Name:

Hissène Habré

Popular Name:

Hissène Habré

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

COVID-19

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Faya-Largeau, French Equatorial Africa (now Chad)

Place of Death:

Dakar, Senegal

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Executive Excellent administrators, unsurpassed at managing things – or people. Habré’s authoritarian control, focus on order, and decisive military leadership align with the “Executive” type, reflecting his pragmatic and commanding nature.

Habré rose to power with support from the United States and France, who saw him as a bulwark against Libyan influence in Africa during the Cold War.

He was overthrown in 1990 by Idriss Déby and fled to Senegal, where he lived in exile for over two decades.

His regime was marked by widespread human rights abuses, including torture, political repression, and the deaths of an estimated 40,000 people.

Hissène Habré was a Chadian politician and military leader who ruled Chad as its president from 1982 to 1990.

In 2016, Habré became the first former African head of state to be convicted of human rights crimes in another African country, sentenced to life in prison for crimes against humanity.

Became President of Chad in 1982.

Defeated Libyan forces in the Toyota War (1987).

Led the FROLINAT rebel group in the 1970s.

Received military training in France.

Served as Prime Minister of Chad in 1978.