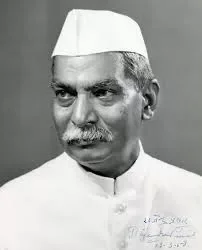

Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

wikipedia.org

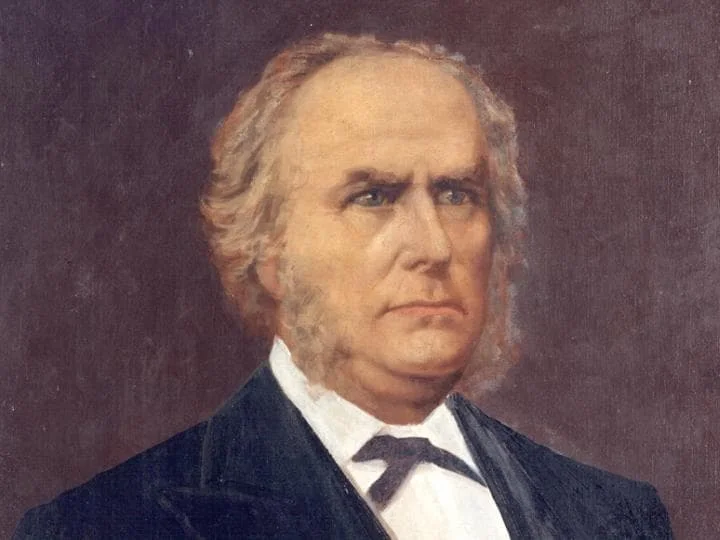

Kwame Nkrumah

Birthday:

21 Sep, 1909

Date of Death:

27 Apr, 1972

Cause of death:

Cancer

Nationality:

Ghanaian

Famous As:

Politician

Age at the time of death:

62

Francis Nwia-Kofi Ngonloma's Quote's

Early Life: Roots of Resolve

Kwame Nkrumah was the heartbeat of a continent yearning for self-determination. A fiery orator with a philosopher’s mind, Nkrumah fused Pan-African dreams with grassroots activism, forging a movement that rippled far beyond the borders of his homeland. To many, he was the man who lit the torch of African independence in the 20th century. To others, he was a relentless idealist whose ambitions sometimes outran the political winds. But above all, Nkrumah was a man possessed by a singular, uncompromising vision: a free and united Africa.

Born on September 21, 1909, in Nkroful, a small village nestled along the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana), Nkrumah’s origins were unassuming. He was the only child of his mother, Nyaniba, a fishmonger of the Nzema ethnic group, and his father, a goldsmith whose name history did not preserve. Raised in a matrilineal society, young Nkrumah was nurtured by a close-knit extended family steeped in traditional values but increasingly influenced by Western missionary education.

Even as a child, Nkrumah was deeply contemplative. Locals would recall how he could sit for hours, seemingly lost in thought, while others played. His first spark of political consciousness ignited during British colonial rule, when racial discrimination and economic disparity were everyday realities. In an odd twist of fate, his name—Kwame, meaning “born on a Saturday”—would become synonymous with Monday morning revolutions.

Education as a Weapon: Books, Battles, and Blackboards

Education was Nkrumah’s ladder out of poverty, and he climbed it with determination. He attended the Roman Catholic elementary school in Half Assini before moving on to the revered Achimota School in Accra. But it was at the Prince of Wales College (now University of Sierra Leone), where he trained as a teacher, that his intellectual curiosity truly began to burn.

Yet Ghana was too small for the dreams swelling inside him. In 1935, with little money but enormous ambition, he sailed to the United States to study at Lincoln University, a historically Black college in Pennsylvania. Working odd jobs, including mopping floors and washing dishes. He paid his way through school, eventually earning multiple degrees in theology, philosophy, and education.

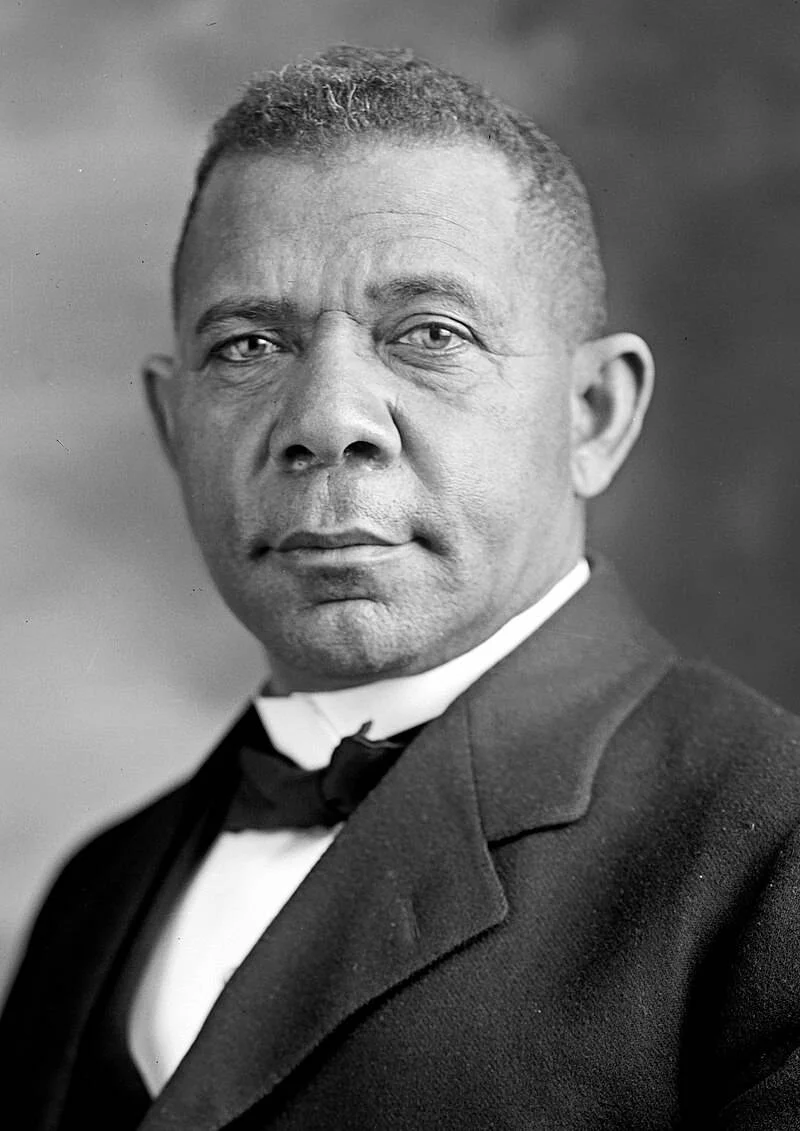

His time in America was transformational. There, he absorbed the writings of Karl Marx, Marcus Garvey, and W.E.B. Du Bois, forming a potent blend of socialism and Black nationalism. He even formed the African Students Association, which became a hub for anti-colonial dialogue. Nkrumah’s political awakening was no accident—it was the product of study, struggle, and sleepless nights spent wrestling with the contradictions of empire and liberation.

The Road to Independence: From Organiser to Liberator

When Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast in 1947, the air was thick with unrest. He joined the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) as general secretary but quickly clashed with its moderate leadership. In 1949, he broke away and founded the Convention People's Party (CPP), promising “self-government now.” His charisma and connection to the common people, often calling himself the “voice of the voiceless”, ignited a populist movement unlike any other in colonial Africa.

British authorities, alarmed by his influence, jailed him in 1950. Ironically, that only amplified his stature. While still behind bars, he was elected to parliament in a landslide. In 1957, Nkrumah stood at the podium of a newly independent Ghana, proclaiming: “At long last, the battle has ended, and Ghana, our beloved country, is free forever.”

The Pan-African Vision

Ghana's independence was just the beginning. Nkrumah believed political freedom was hollow without economic independence, and national liberation incomplete without continental unity. He poured resources into education, infrastructure, and industrialisation—building the Akosombo Dam, expanding healthcare, and promoting science and technology.

He also invited revolutionaries and thinkers from across the African diaspora, including Malcolm X and Che Guevara, to Accra, transforming the city into an intellectual mecca. In 1963, he helped found the Organization of African Unity (OAU), laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the African Union.

Yet his dreams came at a cost. Massive government spending strained the economy, and his increasingly autocratic tendencies, which included a one-party state and preventive detention laws, eroded domestic support. In 1966, while on a peace mission to Vietnam, his government was overthrown in a military coup.

Exile and the Echoes of Revolution

Nkrumah never returned to Ghana. He lived the rest of his life in Conakry, Guinea, as a guest of President Sékou Touré, who named him honorary co-president. He continued to write, penning influential books like Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, and advising other liberation movements from afar.

Despite isolation and illness, his vision for Africa never dimmed. He died on April 27, 1972, in Bucharest, Romania, of cancer. He was 62 years old.

Personal life: The Man Behind the Mission

Away from the podium and parades, Nkrumah was a complex, philosophical, driven, and deeply private. He married Fathia Rizk, an Egyptian Coptic Christian, in a politically symbolic union that represented his dream of African unity from Cairo to Cape Town. They had three children together, though political turmoil eventually separated them.

A lesser-known fact? He was a fan of jazz and often retreated into the rhythms of African-American music, which he said helped him think more clearly. He also kept a meticulously organized bookshelf, with works ranging from Plato to Tagore.

Legacy: A Flame That Refused to Die

Kwame Nkrumah's legacy is a paradox, marked by both triumph and tragedy. He is remembered as the father of Ghanaian independence, the architect of modern Pan-Africanism, and one of the most influential African leaders of the 20th century. His portrait hangs in African Union headquarters, and his speeches are still taught in classrooms from Accra to Addis Ababa.

In recent years, Ghana has sought to reconcile with its past, honouring Nkrumah with statues, holidays, and a mausoleum in Accra that draws thousands of visitors. His ideas, once dismissed as utopian, now resonate anew as Africa grapples with unity, neocolonialism, and the meaning of true independence.

In life, Kwame Nkrumah dared to dream of an Africa that stood tall and together. In death, he remains its eternal symbol of defiance, dignity, and destiny.

Name:

Francis Nwia-Kofi Ngonloma

Popular Name:

Kwame Nkrumah

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

Cancer

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Nkroful, Ghana

Place of Death:

Bucharest, Romania

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Commander: Kwame Nkrumah was a bold, visionary leader with a strategic mind, relentlessly pursuing the goal of a united, independent Africa, never deterred by obstacles and always focused on making his grand vision a reality.

He was so passionate about African unity that he carried a map of a unified Africa everywhere he went.

His autobiography, "Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah," was written while he was in prison.

Nkrumah once studied under and was heavily influenced by Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, whom he later invited to live and be buried in Ghana.

He was instrumental in founding the Organization of African Unity in 1963, laying the groundwork for today's African Union.

In 2000, he was posthumously named “Africa’s Man of the Millennium” by BBC World Service listeners for his role in Africa’s liberation movements.

Kwame Nkrumah led Ghana to become the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence from colonial rule in 1957, marking a historic milestone for the continent.

Under his leadership, Ghana saw major infrastructure development, including the Akosombo Dam, which transformed the country’s energy and industrial capacity.