Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

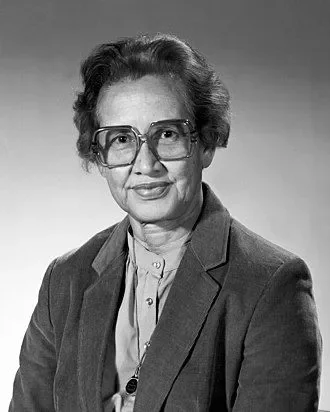

source:wikimedia.org

Barbara McClintock

Birthday:

16 Jun, 1902

Date of Death:

02 Sep, 1992

Cause of death:

Natural causes

Nationality:

American

Famous As:

Cytogeneticist

Age at the time of death:

90

Barbara McClintock's Quote's

Barbara McClintock: A Pioneer in Genetics

Barbara McClintock, born Eleanor McClintock on June 16, 1902, in Hartford, Connecticut. She was an American scientist who revolutionized the field of genetics. In 1983, she won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her groundbreaking work on maize genetics and the identification of transposable genetic elements. She was the first woman to win this prize without sharing it.

Early Life and Education

McClintock grew up in a family that valued education and independence. Her father, Thomas Henry McClintock, was a physician, and her mother, Sara Handy McClintock, was a pianist. Even as a child, Barbara was already inclined towards independent thought and spending time alone. Because of her unique personality, her parents decided to call her Barbara, not Eleanor, when she was only a few months old.

Her mother’s initial opposition, based on concerns that higher education would hinder Barbara’s marriage prospects, didn’t deter her from enrolling at Cornell’s College of Agriculture in 1923. Her passion for genetics blossomed there, leading to exceptional academic performance. In 1923, she received her bachelor’s degree in botany, specializing in genetics; this was followed by a master’s in 1925 and a doctorate in 1927.

Professional Career and Achievements

McClintock started her genetics career at Cornell, where she created the field of maize cytogenetics. She and Harriet Creighton gave the first experimental proof of genes’ chromosomal location in 1931. Her groundbreaking work made her a leading figure in the field.

McClintock began working at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York in 1941, remaining there for the duration of her career. Here, she found what would become her most important discovery—”jumping genes” or transposable genetic elements. This transformative concept contradicted the accepted view of genes as static, orderly components of chromosomes.

Major Contributions and Impact

The scientific community initially reacted to McClintock’s discovery of transposable elements with skepticism. Her persistence and careful research ultimately led to the acceptance of her findings. This finding has profoundly influenced genetics and underpins a significant portion of modern genetic engineering.

McClintock was awarded many honors during her career. In 1944, she became only the third woman to be elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In 1945, she became the first woman president of the Genetics Society of America.

Personal Life

McClintock’s life was dedicated to her research, not marriage. Her independent spirit and unconventional approach to life and science were well-known. Colleagues characterized her as intuitive and spiritual, highlighting her belief in trusting instincts in science.

Later Years and Legacy

Barbara McClintock pursued her research at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory until she retired. She passed away on September 2, 1992, in Huntington, New York, at the age of 90.

McClintock is remembered for more than just her scientific achievements. Her persistence and innovative thinking have overcome societal barriers, inspiring women in science. Her life and achievements are still honored, appearing on U.S. stamps and in countless biographies and children’s books.

Barbara McClintock’s path, from a curious Hartford child to a Nobel laureate, exemplifies dedication, independent thought, and groundbreaking research’s power to expand human knowledge.

Name:

Barbara McClintock

Popular Name:

Barbara McClintock

Gender:

Female

Cause of Death:

Natural causes

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Hartford, Connecticut, USA

Place of Death:

Huntington, New York, USA

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Logician: Innovative inventors with an unquenchable thirst for knowledge. McClintock exhibited traits of deep curiosity, independence, and analytical thinking, preferring solitary research over social collaboration, with a focus on complex problem-solving and innovation.

Her parents changed her birth name from Eleanor to Barbara, believing it better suited her strong personality.

She lived in two rooms above a garage for 20 years despite her scientific success.

She trained Latin American cytologists to preserve indigenous maize strains in the late 1950s.

She was an avid reader of diverse topics, including Tibetan Buddhism.

Awarded the National Medal of Science in 1971.

Discovered transposable elements in maize.

Elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1944.

First woman president of the Genetics Society of America in 1945.

Received the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.