Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

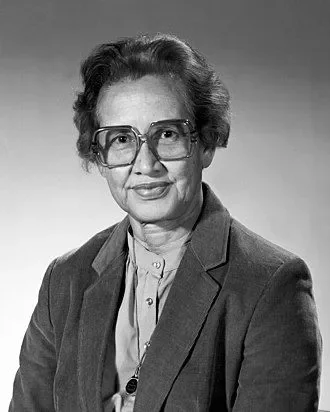

source:wikimedia.org

Dorothy Hodgkin

Birthday:

12 May, 1910

Date of Death:

29 Jul, 1994

Cause of death:

Natural causes (following a stroke)

Nationality:

British

Famous As:

Chemist

Age at the time of death:

84

Dorothy Hodgkin's Quote's

Dorothy Hodgkin: A Pioneering Crystallographer

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, born on May 12, 1910, in Cairo, Egypt, was an English chemist who revolutionized the field of X-ray crystallography. In 1964, she became the first British woman to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, a result of her innovative work on essential biochemical compounds.

Early Life and Education

A large portion of Dorothy’s childhood was spent in the Middle East and North Africa, where she was raised by her English parents, John and Grace Crowfoot. Her father’s work as a school inspector and her parents’ passion for archaeology exposed her to diverse cultures from an early age. Her mother’s gift of a portable mineral-analysis kit fostered a childhood fascination with minerals and crystals, leading to her future career.

Dorothy received her formal education in England. At the age of 15, she received Sir William Henry Bragg’s book “Concerning the Nature of Things,” which sparked her interest in using X-rays to study atomic structures. Her whole scientific career was shaped by this early exposure.

Academic Journey

In 1928, Dorothy’s strong academic performance secured her a place at Somerville College, Oxford. She became only the third woman to receive a first-class honors degree in chemistry from the institution. Cambridge University awarded her a PhD under the supervision of J D Bernal, a leading figure in molecular biology.

Personal Life

In 1937, Dorothy married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, a historian’s son. Their marriage was happy, even though it was considered unconventional at the time. Three children were born to the couple: Luke in 1938, Elizabeth in 1941, and Toby in 1946. Thomas frequently traveled abroad for work, especially to West Africa, yet the Hodgkins always kept a hospitable home, frequently entertaining students and international guests.

Professional Achievements

Dorothy made many groundbreaking discoveries throughout her career. The structure of penicillin was solved in 1945 by her and her colleagues, contradicting common scientific beliefs. Her most significant accomplishment was deciphering the vitamin B12 structure in 1954, a feat Lawrence Bragg compared to breaking the sound barrier.

Hodgkin conquered considerable challenges throughout her career. At the age of 24, she was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that would progressively worsen over time. Although physically limited, she persevered, inventively creating her own tools to operate lab equipment.

Impact and Legacy

Hodgkin’s work laid the foundation for modern structural biology. Her findings have significantly impacted various fields, including medicine and materials science. In addition to her scientific work, she passionately advocated for global cooperation in science and nuclear arms reduction.

Dorothy Hodgkin passed away on July 29, 1994, in Shipston-on-Stour, United Kingdom, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire scientists worldwide.

Interesting Anecdotes

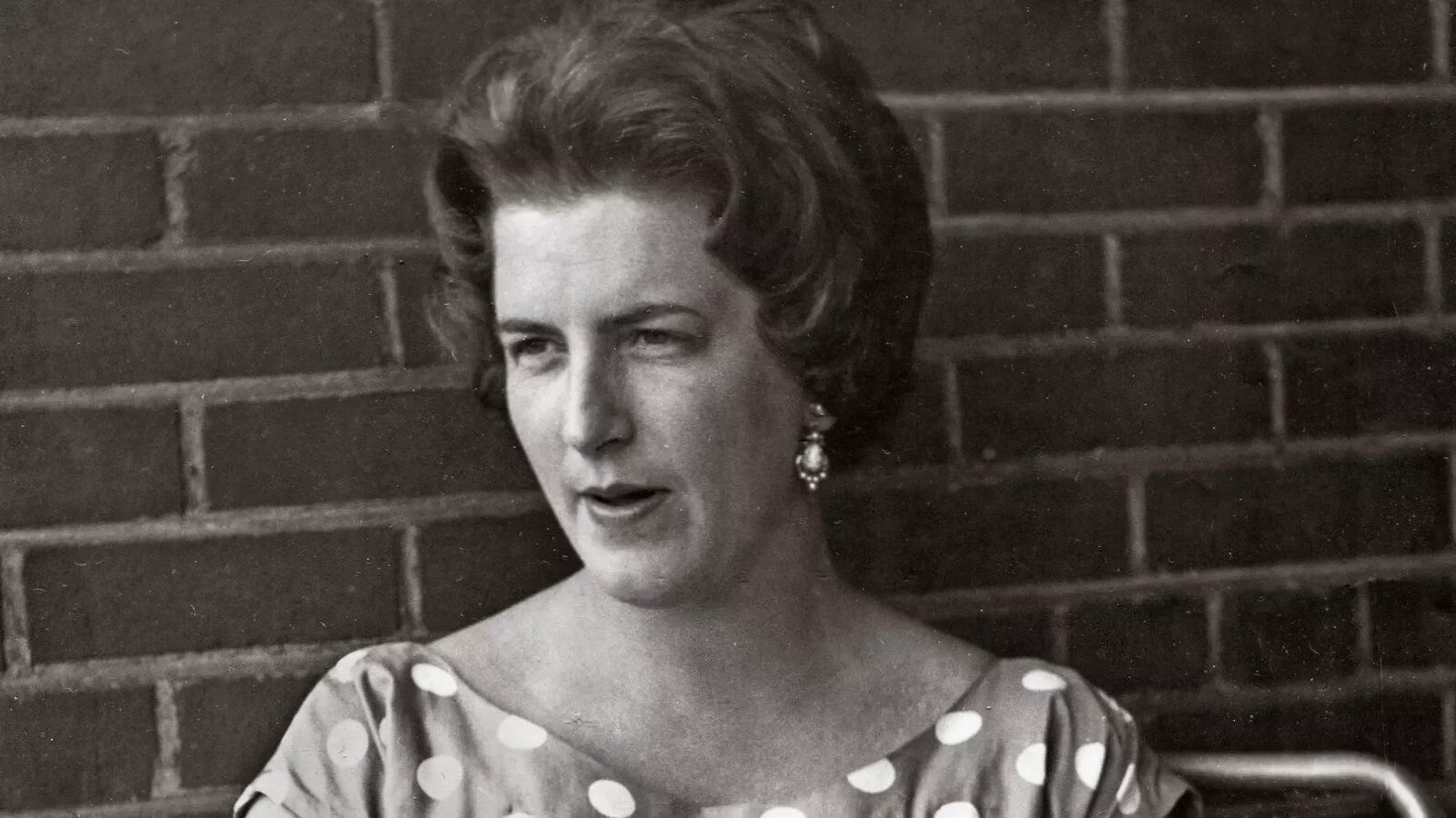

Margaret Thatcher, who was once a student of Hodgkin, later became the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Although Hodgkin and Thatcher held opposing political beliefs—Hodgkin was a Labour supporter—Thatcher still displayed her portrait in her office to show her respect.

Hodgkin’s dedication to deciphering insulin’s structure is shown by her 34 years of work, culminating in success in 1969. She showed remarkable persistence in science and life, conquering both physical challenges and doubters to make significant breakthroughs.

Hodgkin’s biography showcases scientific genius, unwavering determination, and a commitment to using knowledge to benefit humanity. Her professional legacy shapes modern science, and her personal story inspires future researchers.

.

Name:

Dorothy Hodgkin

Popular Name:

Dorothy Hodgkin

Gender:

Female

Cause of Death:

Natural causes (following a stroke)

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Cairo, Egypt (then under British administration)

Place of Death:

Ilmington, Warwickshire, England

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Advocate: Quiet and mystical, yet very inspiring and tireless idealists. Hodgkin’s quiet determination, empathy (seen in her pacifism and mentorship), and visionary approach to science suggest a personality blending insight with a commitment to improving lives.

Her childhood in Egypt sparked her love for archaeology alongside chemistry.

She developed rheumatoid arthritis at age 28, yet continued lab work with deformed hands.

She mentored a young Margaret Thatcher in chemistry at Oxford.

She was banned from U.S. travel in the 1950s due to her communist sympathies.

Awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society in 1976.

Determined the structure of penicillin in 1945

Elucidated the structure of vitamin B12 in 1956

Received the Order of Merit in 1965

Won the 1964 Nobel Prize in Chemistry