Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

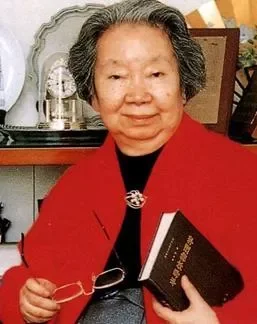

source:wikimedia.org

Irène Joliot-Curie

Birthday:

12 Sep, 1897

Date of Death:

17 Mar, 1956

Cause of death:

Leukemia

Nationality:

French

Famous As:

Chemist

Age at the time of death:

58

Irene Joliot Curie's Quote's

Irene Joliot-Curie: Early Life and Education

Irene Joliot-Curie, born Irène Curie on September 12, 1897, in Paris, France, was a renowned French chemist and physicist. Being the daughter of Nobel laureates Pierre and Marie Curie, Irene was always expected to achieve great things.

Unlike most children, Irene grew up surrounded by scientific genius at home. Her mother hired scientists to give her an unconventional education in physics, math, and other subjects. Irene’s father, Pierre, died in a street accident when she was just eight years old. This loss brought her closer to her grandfather, Dr. Eugène Curie, who became her first teacher and best friend.

Irene’s formal education was interrupted by World War I, during which she worked with her mother as a nurse radiographer. Following the war, she went back to the Sorbonne to study, receiving her doctorate in 1925 for a thesis about polonium alpha rays.

Personal Life and Marriage

In 1926, Irene married Frédéric Joliot, a fellow scientist who had joined her mother’s Radium Institute. Joliot-Curie became the couple’s shared surname, marking the start of a successful personal and professional collaboration. They had two children, Hélène and Pierre, who would later become physicists themselves.

Professional Career and Achievements

Irene made significant contributions and groundbreaking research in the field of radioactivity throughout her career. With her husband’s close assistance, she made several important findings.

The Joliot-Curies’ most famous discovery, artificial radioactivity, was made in 1934. They discovered that alpha particle bombardment could make stable elements radioactive. Their groundbreaking achievement led to the award of the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, further enhancing the Curie family’s remarkable collection of Nobel Prizes.

Major Contributions and Impact

Irene’s work had far-reaching implications in various fields:

Medicine: The field of medicine advanced with the discovery of artificial radioactivity, leading to the use of radioactive isotopes in treatments and diagnostics.

Nuclear Physics: Her work on nuclear fission made a significant contribution to its understanding, forming a foundation for future progress in nuclear energy.

World War II: Her earlier research played a crucial role in developing the atomic bomb, even though she wasn’t directly part of the Manhattan Project.

In addition to her scientific achievements, Irene was a pioneer for women in both science and politics. In 1936, she became one of the first three female French government officials.

Later Years and Legacy

Irene’s health was tragically damaged by years of exposure to radioactive materials. She was diagnosed with leukemia, likely caused by exposure to polonium in a laboratory accident in 1946. Though her health was failing, Irene still worked, even designing new physics labs at Orsay in 1955.

Irene Joliot-Curie passed away on March 17, 1956, in Paris at the age of 58. She’s remembered for her science and for inspiring women in the field. The Joliot-Curies’ discoveries, fundamental to modern nuclear physics and chemistry, continue to shape advancements in fields like medicine and energy.

Today, Irene Joliot-Curie is remembered as a brilliant scientist who carried forward her family’s legacy while making her own significant mark on the world of science.

Name:

Irene Joliot Curie

Popular Name:

Irène Joliot-Curie

Gender:

Female

Cause of Death:

Leukemia

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Paris, France

Place of Death:

Paris, France

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Her daughter, Hélène Langevin-Joliot, also became a nuclear physicist.

She narrowly missed discovering the neutron, a feat later credited to James Chadwick.

She served as a nurse radiographer during World War I, exposing herself to radiation early on.

She was an outspoken feminist and briefly served as Undersecretary of State for Scientific Research in France in 1936.

Co-discovered artificial radioactivity in 1934.

Elected to the French Academy of Sciences in 1951.

Received the Lavoisier Medal from the French Chemical Society.

Served as a Commissioner for Atomic Energy in France (1946–1950).

Won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935 with Frédéric Joliot-Curie.