Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

source:.britannica.com

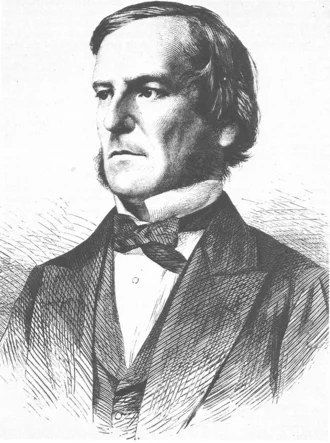

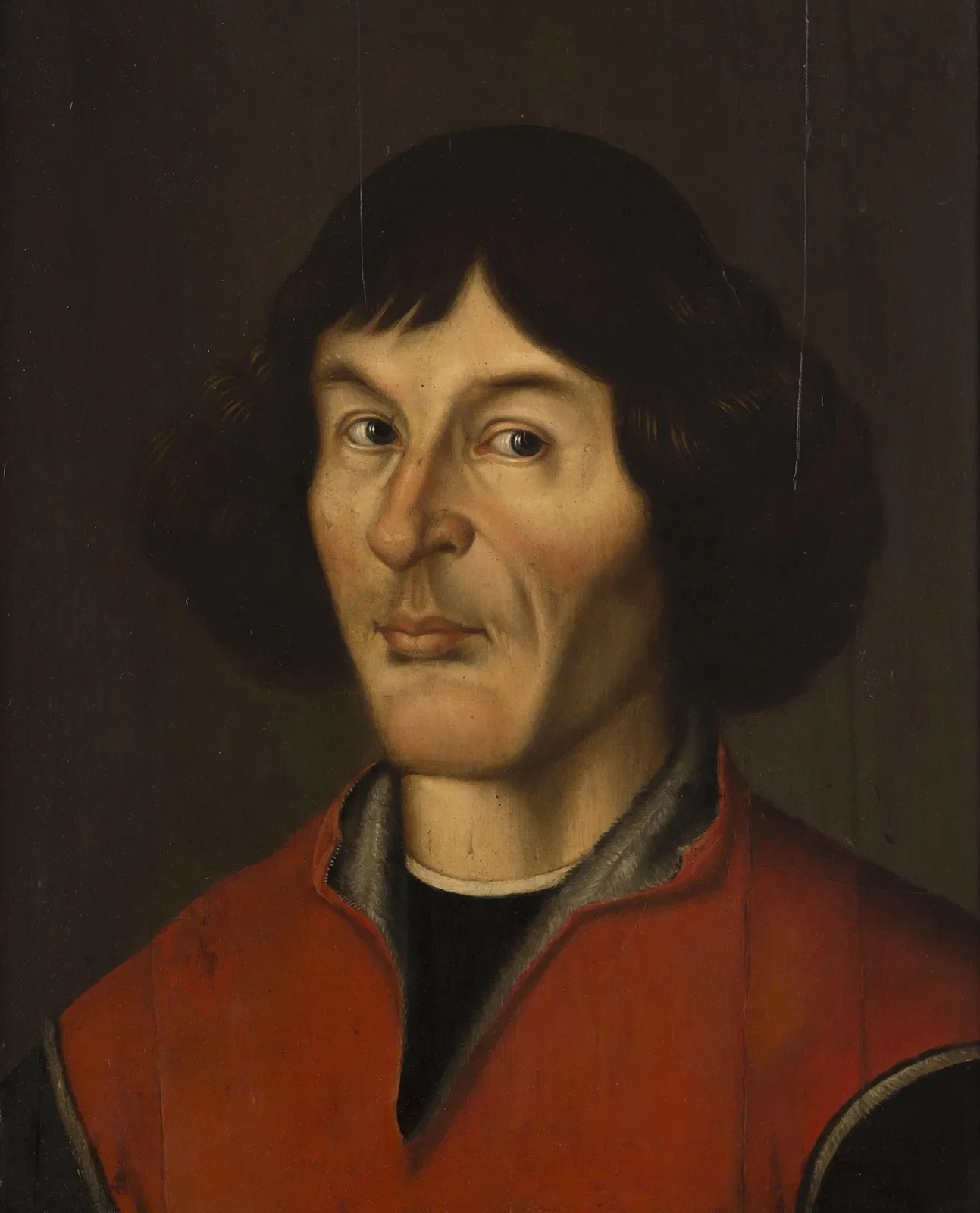

Nicolaus Copernicus

Birthday:

19 Feb, 1473

Date of Death:

24 May, 1543

Cause of death:

cerebral hemorrhage

Nationality:

Polish

Famous As:

Astronomer

Age at the time of death:

70

Nicolaus Copernicus's Quote's

Early Life: A Mind Shaped by Order and Curiosity

In a time when the Earth was believed to sit immovable at the center of the universe, Nicolaus Copernicus dared to imagine a cosmos where our planet danced among others, revolving around the sun. He was not a rebel with banners or a man of fanfare, but a quiet thinker whose revolutionary ideas rewrote the heavens. With one bold theory, Copernicus helped shift humanity’s understanding of its place in the universe—and launched the scientific revolution.

Nicolaus Copernicus was born on February 19, 1473, in the bustling port town of Toruń in Royal Prussia, part of the Kingdom of Poland. He was the youngest of four children in a well-off merchant family. His father died when Nicolaus was around ten, and he was taken under the care of his maternal uncle, Lucas Watzenrode, a canon in the Catholic Church who would go on to become the Bishop of Warmia. This uncle recognized Nicolaus’s potential early and ensured he received a first-rate education.

Even as a child, Copernicus was known for his meticulous nature. He had a habit of organizing objects, observing the stars, and keeping detailed notes—traits that hinted at the celestial order he would one day uncover.

Education: A Scholar of Many Disciplines

Copernicus’s educational journey spanned Europe and the intellectual spectrum. He studied at the University of Kraków around 1491, where he was introduced to mathematics and astronomy. It was here that he first encountered the geocentric (Earth-centered) model of the cosmos, taught as dogma. But even then, he began to question its inconsistencies.

He later studied law and medicine in Italy, at Bologna and Padua, and earned a doctorate in canon law from the University of Ferrara. Yet astronomy remained his quiet obsession. During his time in Bologna, he lived with the astronomer Domenico Maria Novara, assisting with celestial observations and feeding his skepticism of the Ptolemaic model.

Trivia: Copernicus was multilingual and fluent in Latin, Polish, German, and Greek. He once translated a Greek poem into Latin just to prove a scholarly point.

Career Journey: Canon by Title, Astronomer by Calling

Early Career: Balancing Church and Stars

Copernicus returned to Poland in the early 1500s and served as a canon of the Frombork Cathedral, a position secured by his uncle. While his official duties included church administration and overseeing estates, he quietly turned a room in his tower into an observatory.

Despite not being a professional astronomer by today’s standards, Copernicus made remarkably precise observations—often without a telescope, which had yet to be invented. He used simple instruments like quadrants and armillary spheres to track planetary motion.

The Heliocentric Theory: A Cosmos Reimagined

For centuries, the Ptolemaic model, which placed Earth at the center of the universe, had been unchallenged. But Copernicus found its epicycles—those strange little orbits within orbits—illogical and unwieldy. After decades of calculations and careful thought, he proposed a radical idea: the sun, not the Earth, was at the center of the universe.

He outlined this theory in his magnum opus, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), which he worked on for more than 30 years. Afraid of the Church’s reaction, Copernicus delayed publication. It was only in 1543, the year of his death, that the book was finally printed.

Trivia: Legend says a copy of De revolutionibus was placed in Copernicus’s hands on his deathbed. He saw it just before passing away.

Personal Life: The Quiet Revolutionary

Copernicus never married and lived a relatively private life. He was known to be introverted, methodical, and deeply devoted to study. He had close friendships but kept a respectful distance from public controversy.

Interestingly, Copernicus also dabbled in economics. In 1517, he wrote a treatise on inflation and currency devaluation—centuries ahead of his time—which later influenced monetary policy thinkers.

Despite his scientific leanings, he remained a devout Catholic. His work, he believed, was a path to better understanding the order of God’s universe—not defiance of faith.

Legacy: The Man Who Set the Universe in Motion

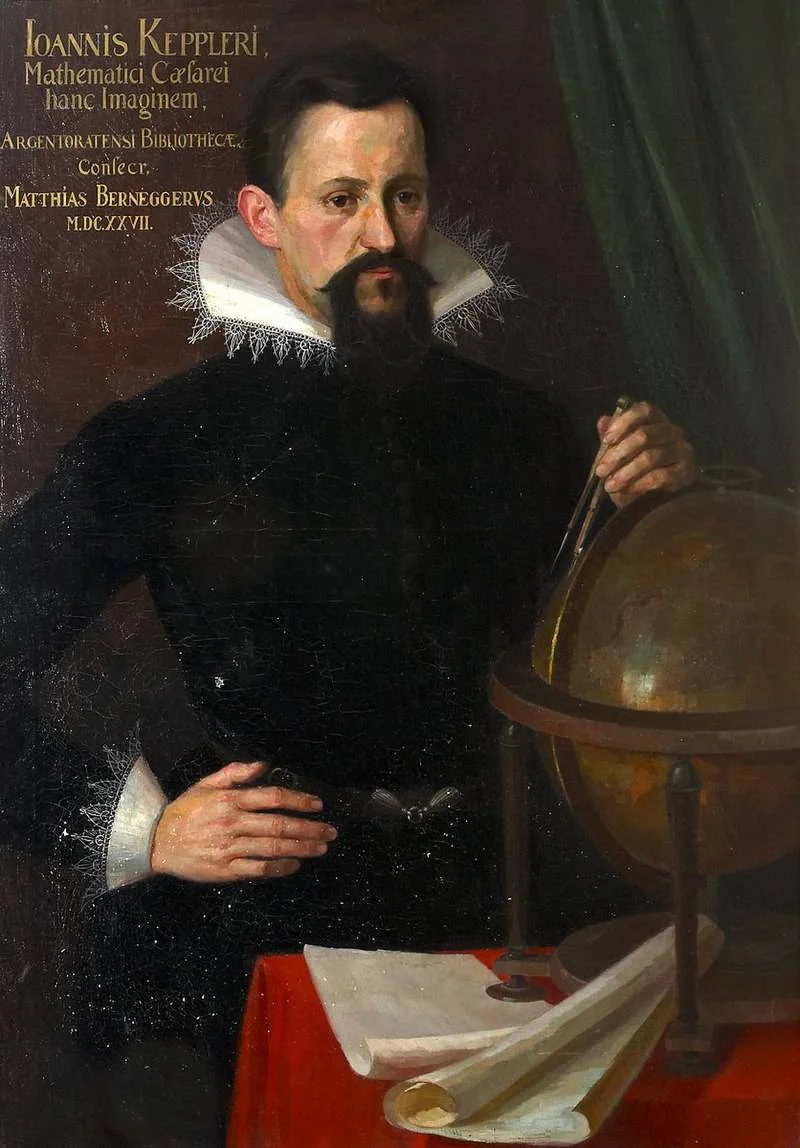

Copernicus died on May 24, 1543, just as his ideas began to reach the world. His heliocentric model didn’t gain widespread acceptance immediately—indeed, it was banned by the Catholic Church for a time—but it laid the foundation for astronomers like Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton.

The “Copernican Revolution” wasn’t just a scientific shift—it was a philosophical earthquake. It dethroned Earth from the center of creation and challenged the human ego, sparking an era of inquiry, discovery, and doubt that would become the Scientific Revolution.

Trivia: The phrase “Copernican Revolution” is now used metaphorically to describe any profound paradigm shift in human thought.

Conclusion: A Mind That Reshaped the Heavens

Nicolaus Copernicus changed the universe not by force, but by thought. In an age when challenging authority was dangerous, he offered a model of truth built on patience, observation, and quiet conviction. His sun-centered universe turned the world upside down—and in doing so, helped it find its rightful place in the vastness of space.

With his eyes to the stars and his feet planted in reason, Copernicus redefined not just astronomy, but humanity’s sense of itself. He didn’t just move the Earth—he moved the minds of those who followed.

Name:

Nicolaus Copernicus

Popular Name:

Nicolaus Copernicus

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

cerebral hemorrhage

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Thorn, Royal Prussia, Poland

Place of Death:

Frauenburg, Royal Prussia, Poland

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Debater: Smart and curious thinkers who cannot resist an intellectual challenge. He was intelligent and was curious.

He was a Multilingual Person and knew about five languages.

Nicolaus Copernicus attended four universities before earning a degree.

Nicolaus Copernicus practiced medicine. Without a medical degree.

He also proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis

He Developed a system for calculating and predicting planetary motions

He put forth the heliocentric model of the solar system.