Real Celebrities Never Die!

OR

Search For Past Celebrities Whose Birthday You Share

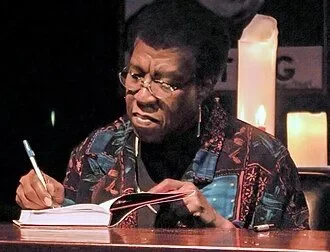

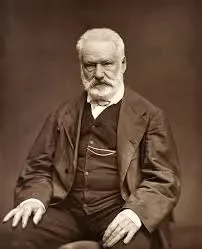

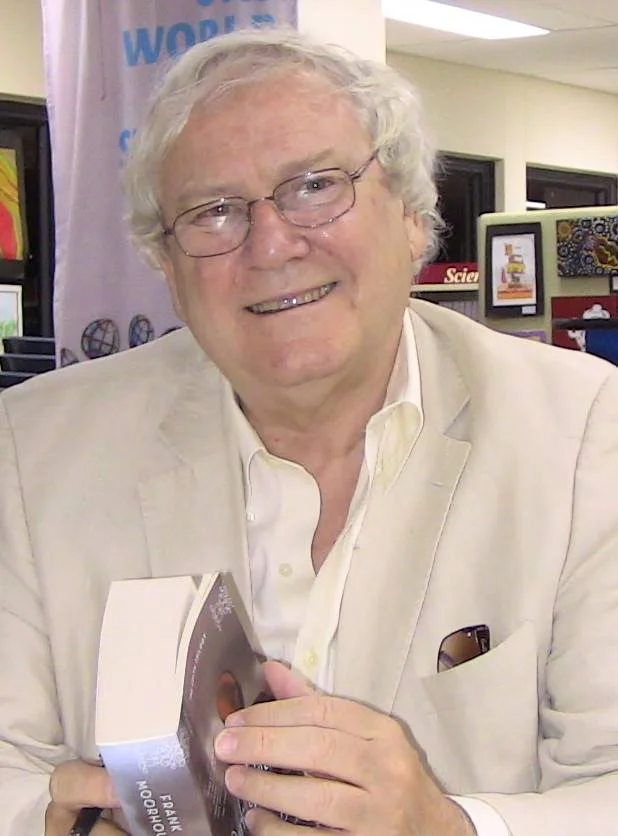

source:wikimedia.org

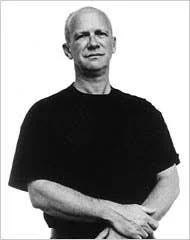

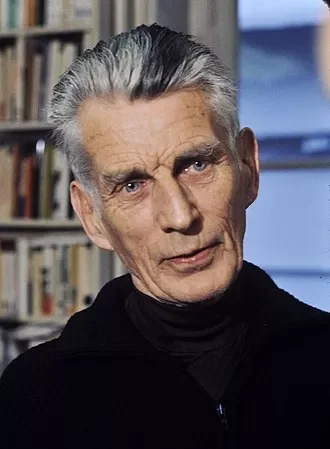

Samuel Beckett

Birthday:

13 Apr, 1906

Date of Death:

22 Dec, 1989

Cause of death:

Emphysema

Nationality:

Irish

Famous As:

Novelist

Age at the time of death:

83

Samuel Beckett's Quote's

Early Life & Education

Samuel Beckett, an Irish playwright, novelist, poet, and literary translator, etched his name into the annals of 20th-century literature with a style that stripped away the excesses of traditional writing and delved deep into the void of human existence. His works—stark, minimalist, and infused with a wry, often dark humor—uncovered the absurdity of life, where meaning is elusive, and survival often feels futile. Yet, in that bleakness, there is a profound resonance, a quiet acknowledgment that we continue to endure, regardless of the circumstances.

This is the genius of Beckett, a man whose creative journey began in Dublin but soon took him to the heart of Paris, where his encounters with literary giants would spark the flames of his own revolutionary writing. In 1969, his contribution to literature was cemented with the Nobel Prize in Literature, but the true legacy of Beckett is found not in his accolades but in his ability to make us question everything we think we know about life, death, and meaning itself.

Born on April 13, 1906, in Dublin, Samuel Beckett was raised in a middle-class family that, while not financially extravagant, provided a solid foundation for his intellectual pursuits. His father, a civil engineer, and his mother, a teacher, were both keenly focused on education, though they were also emotionally reserved, a characteristic that would influence Beckett’s own internal world. Beckett was the second of three children and often found solace in his studies, particularly literature. He showed early signs of intellectual brilliance, excelling in his academic endeavors, and his years at Dublin’s prestigious Trinity College would prove to be pivotal.

At Trinity, Beckett studied French, and it was here that his love for literature and language blossomed. A pivotal moment in his young life came when he read the works of the French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud, which opened his eyes to the idea that literature could be both meaningful and meaningless at the same time—a theme that would dominate his later works. After completing his studies, Beckett ventured into the world of teaching, first in Dublin and then in London, but it was clear that his true calling lay in the written word, not in the classroom.

Career: The Turning Point (Paris and the Birth of an Artist)

In 1928, Beckett’s life took a major turn when he moved to Paris, a city that would shape much of his creative identity. It was here that he encountered one of the most significant figures in his literary development: James Joyce. Joyce, already a towering presence in the world of modernist literature, became both a mentor and a close friend to Beckett. Under Joyce’s guidance, Beckett began to explore writing on his own terms, developing a distinctive voice that would later become synonymous with his minimalist style.

In Paris, Beckett’s creative fire burned brightly. His first novel, Murphy, was published in 1938 and introduced readers to the dark, absurd humor that would come to define much of his work. Yet, it was World War II that would forever alter the course of Beckett’s life. As the war raged across Europe, Beckett became actively involved in the French Resistance, risking his life to fight against Nazi occupation. For his efforts, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre, a recognition that demonstrated his courage and commitment during one of the most harrowing periods in history. The war left its mark on Beckett, not only in terms of personal experience but also in the profound impact it had on his worldview. This experience would later seep into his writing, where themes of survival, despair, and existential struggle became central.

The Breakthrough: Absurdity and Language

After the war, Beckett retreated into a period of intense solitude, a retreat that led him to produce some of his most celebrated works. It was during this time that he made a bold decision that would shape his entire career: he began writing primarily in French. This decision was not one of convenience, but rather a deliberate act to escape the weight of English literary tradition and to focus purely on the simplicity of language. Works like Molloy (1951) and Malone Dies (1951) reflected this linguistic shift, and in many ways, these works represent the birth of the Theatre of the Absurd—a movement that rejected traditional narrative structure and instead explored the absurdity of human existence.

But it was Waiting for Godot (1953), written in French and later translated into English by Beckett himself, that would make Beckett a household name. The play, often described as a cornerstone of 20th-century theatre, depicted two characters, Vladimir and Estragon, waiting for a mysterious figure named Godot, who never arrives. The play’s minimalist staging, elliptical dialogue, and themes of futility resonated deeply with audiences and critics alike, establishing Beckett as a visionary playwright and thinker.

A Personal Life of Silence and Solitude

Though Beckett’s works spoke volumes, his personal life was far more private. He lived much of his life in relative seclusion, preferring the quiet solitude of his Parisian apartment or rural French retreat over the bustle of social circles. His marriage to Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, a French woman he had known for many years, was one of the few constants in his life. Though Beckett was intensely private and often seemed distant from the world around him, his deep love for Suzanne and their quiet companionship brought him a sense of peace amidst the chaos of his creative mind.

Legacy: A Voice for the Absurd

Beckett’s later years saw him continuing to push the boundaries of literature, experimenting with new forms and ideas. His plays, novels, and poetry were translated into multiple languages, ensuring that his influence would spread far beyond the borders of France and Ireland. His writing continued to explore the themes of human frailty, alienation, and the search for meaning in a world that often seems devoid of it.

In 1969, Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, a fitting recognition of his contributions to the world of letters. Yet, perhaps his greatest legacy lies in the profound effect his work has had on writers, philosophers, and artists across generations. Beckett’s unflinching exploration of human existence—its absurdities, its struggles, and its dark humor—continues to challenge and inspire those who engage with his work.

Samuel Beckett’s legacy is not merely one of literary achievement, but of a relentless search for truth in the face of an often indifferent universe. His works have made us laugh, made us uncomfortable, and made us question the very nature of existence. In the silence of his pages, Beckett found the voice of the modern human condition, and in doing so, he has forever changed the way we understand the world.

Name:

Samuel Beckett

Popular Name:

Samuel Beckett

Gender:

Male

Cause of Death:

Emphysema

Spouse:

Place of Birth:

Foxrock, Dublin, Ireland

Place of Death:

Paris, France

Occupation / Profession:

Personality Type

Logician: Innovative inventors with an unquenchable thirst for knowledge. Beckett was a logical and analytical person who explored ideas and possibilities through abstract thought.

Beckett drove a young André the Giant to school. The two of them bonded over their shared love for cricket.

Beckett was amused by the ominous date of his birth.

He nearly died in Paris after he was stabbed on the streets.

He played two first-class games against Northamptonshire for the University of Dublin in 1925-26 making him the only Nobel Literature Laureate to have played first-class cricket.

He worked as James Joyce’s amanuensis until the two writers had a fallout.

Beckett was awarded the Croix de guerre

He received an honorary doctorate from Trinity College Dublin in 1959

He was awarded the Médaille de la Résistance

He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1969

The house where he lived at in 1934 received an English Heritage Blue Plaque